Melissa Cody

Apr 4 – Sep 9, 2024

- Past

- Exhibition

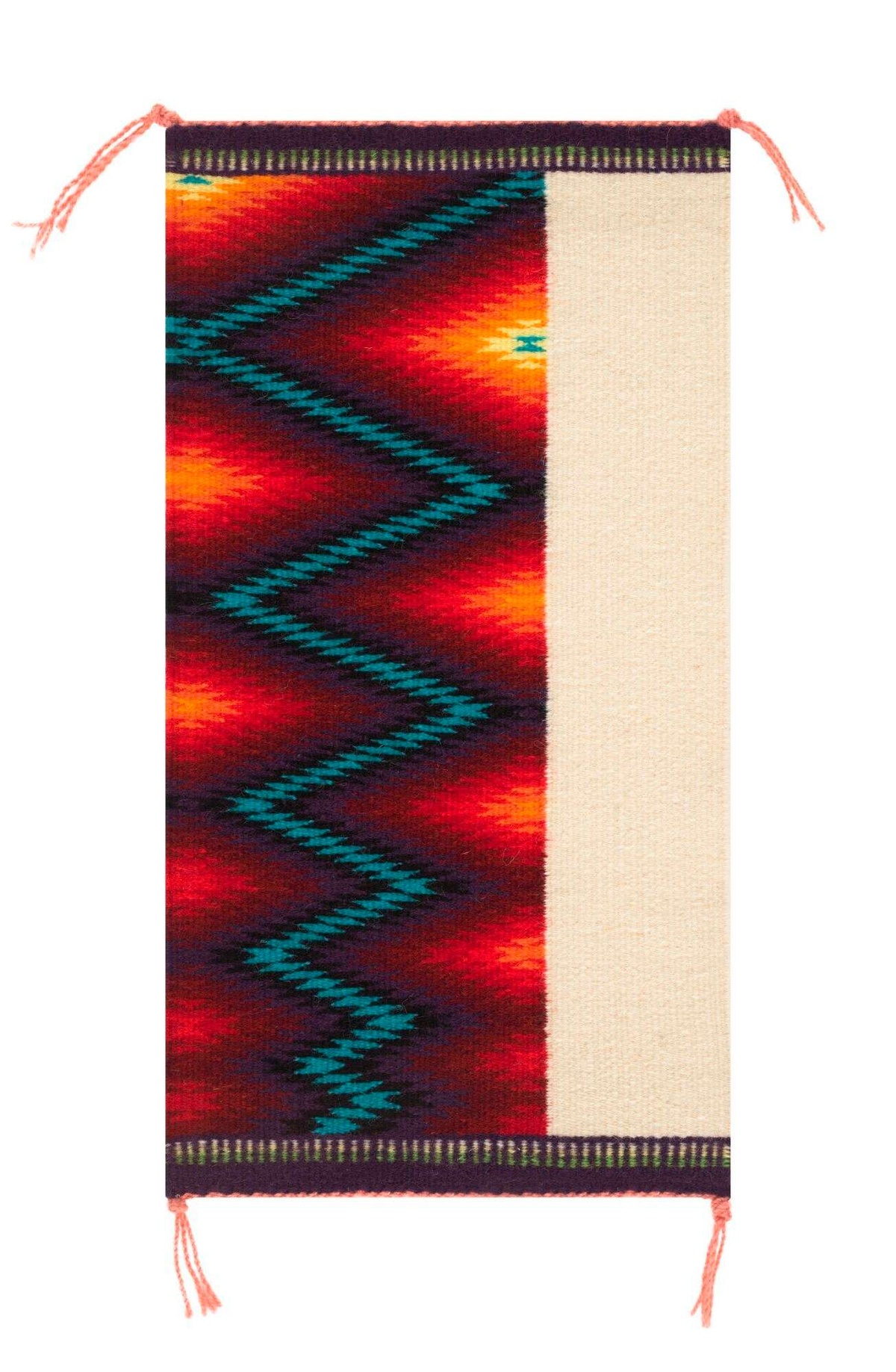

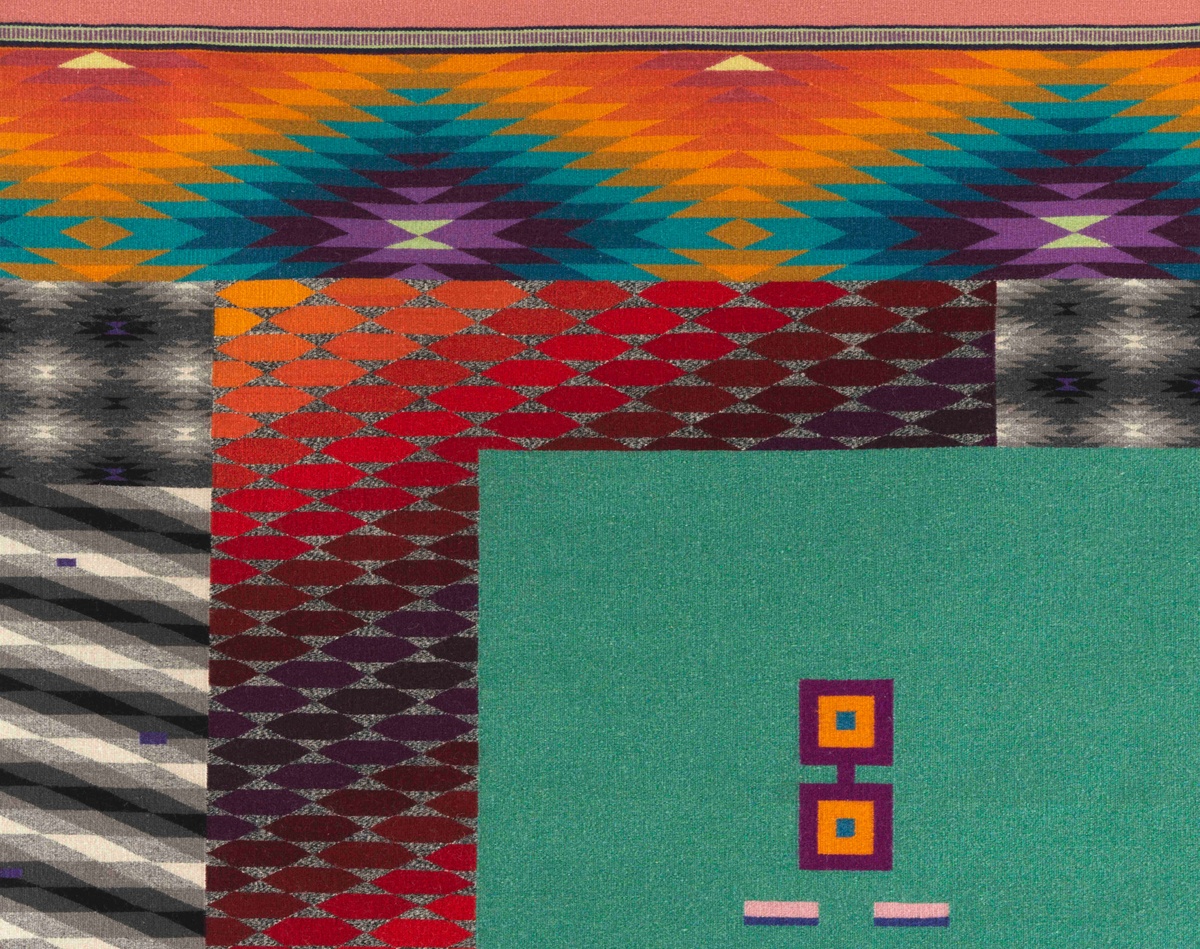

Image: Melissa Cody. Untitled. 2022. Wool warp, weft, selvedge cords, and aniline dyes. 106 x 56 in. (269.2 x 142.2 cm). Cortesía de la artista and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York. Video: Filmed by Elle Rinaldi; Additional footage courtesy of the Hammer Museum; Video Editing by Elle Rinaldi; Audio Recording by Nora Rodriguez; Graphic Design by Julia Schäfer

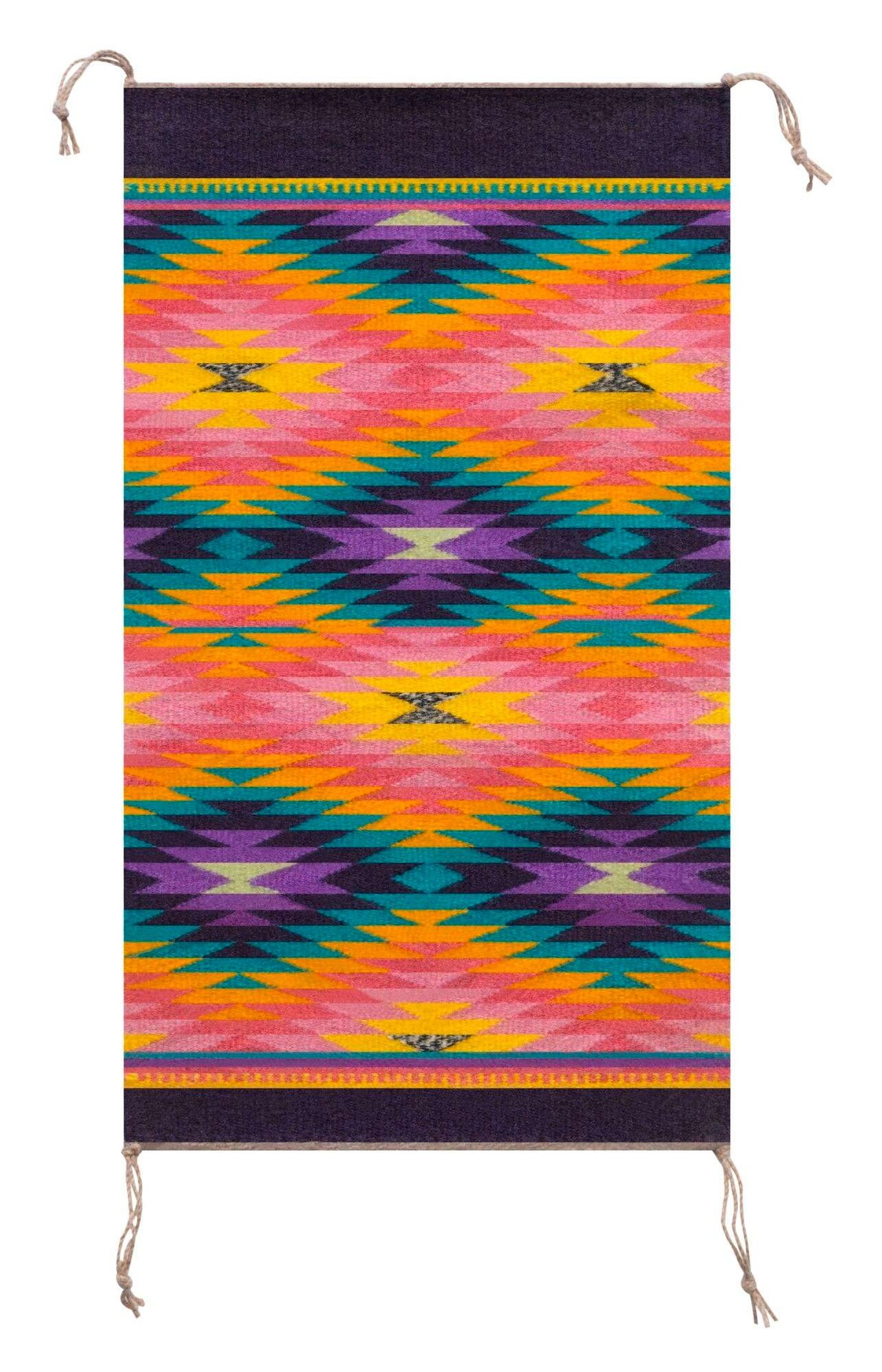

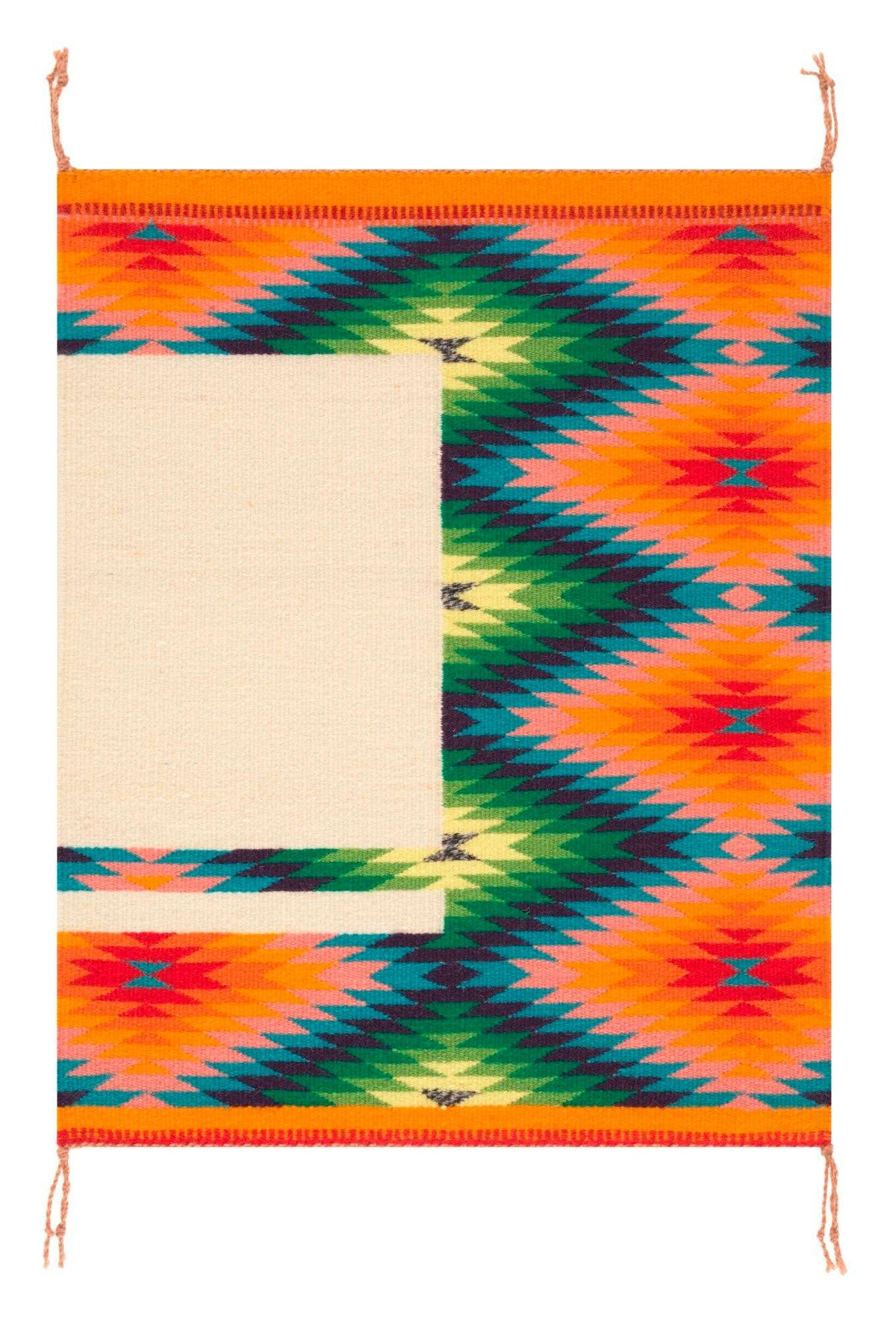

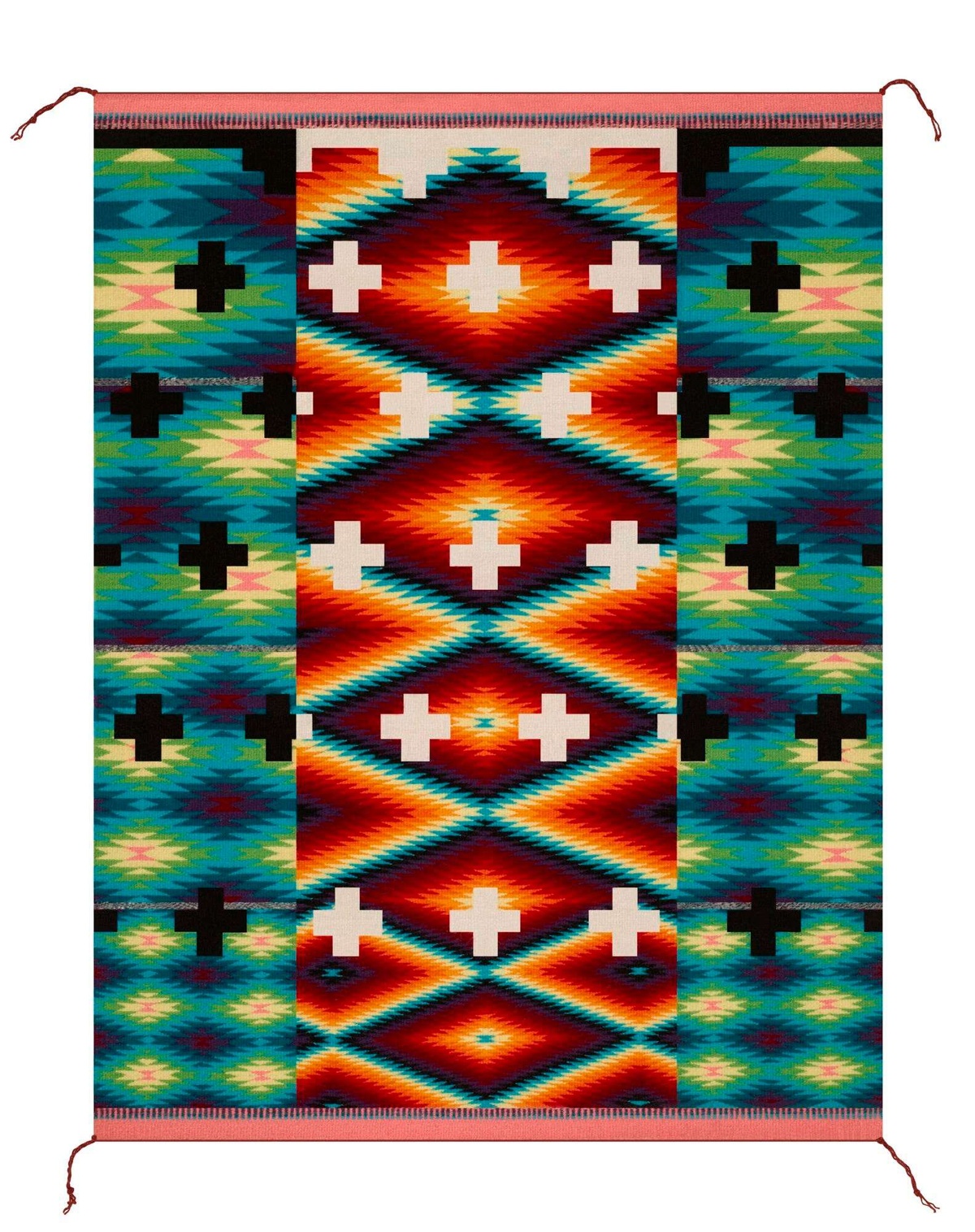

The first major solo museum presentation of fourth-generation Navajo weaver Melissa Cody (b. 1983, No Water Mesa, Arizona) spans the last decade of her practice, showcasing over 30 weavings and a major new work produced for the exhibition. Using long-established weaving techniques and incorporating new digital technologies, Cody assembles and reimagines popular patterns into sophisticated geometric overlays, incorporating atypical dyes and fibers. Her tapestries carry forward the methods of Navajo Germantown weaving, which developed out of the wool and blankets that were made in Germantown, Pennsylvania and supplied by the US government to the Navajo people during the forced expulsion from their territories in the mid-1800s. During this period, the rationed blankets were taken apart and the yarn was used to make new textiles, a practice of reclamation which became the source of the movement. While acknowledging this history and working on a traditional Navajo loom, Cody’s masterful works exercise experimental palettes and patterns that animate through reinvention, reframing traditions as cycles of evolution.

Melissa Cody is a Navajo/Diné textile artist and enrolled member of the Navajo/Diné nation. Cody grew up on a Navajo Reservation in Leupp, Arizona and received a Bachelor’s degree in Studio Arts and Museum Studies from Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe. Her work has been featured in The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia (2022); Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR (2021); National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2019–2020); Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff (2019); SITE Santa Fe (2018–19); Ingham Chapman Gallery, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque (2018); Navajo Nation Museum, Window Rock (2018); and the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe (2017–18). Cody’s works are in the collections of the Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; and The Autry National Center, Los Angeles. In 2020, she earned the Brandford/Elliott Award for Excellence in Fiber Art.

![World Traveler [hi-res].jpg](https://d1tcycker2ppj.cloudfront.net/output=f:jpg,q:60/resize=width:1200,fit:max/pZZnh2STwK1dbgNCVGvu)

![Into the Depths, She Rappels [hi-res].jpg](https://d1tcycker2ppj.cloudfront.net/output=f:jpg,q:60/resize=width:1200,fit:max/g0IUJnGTh6VfSlOHg6k7)