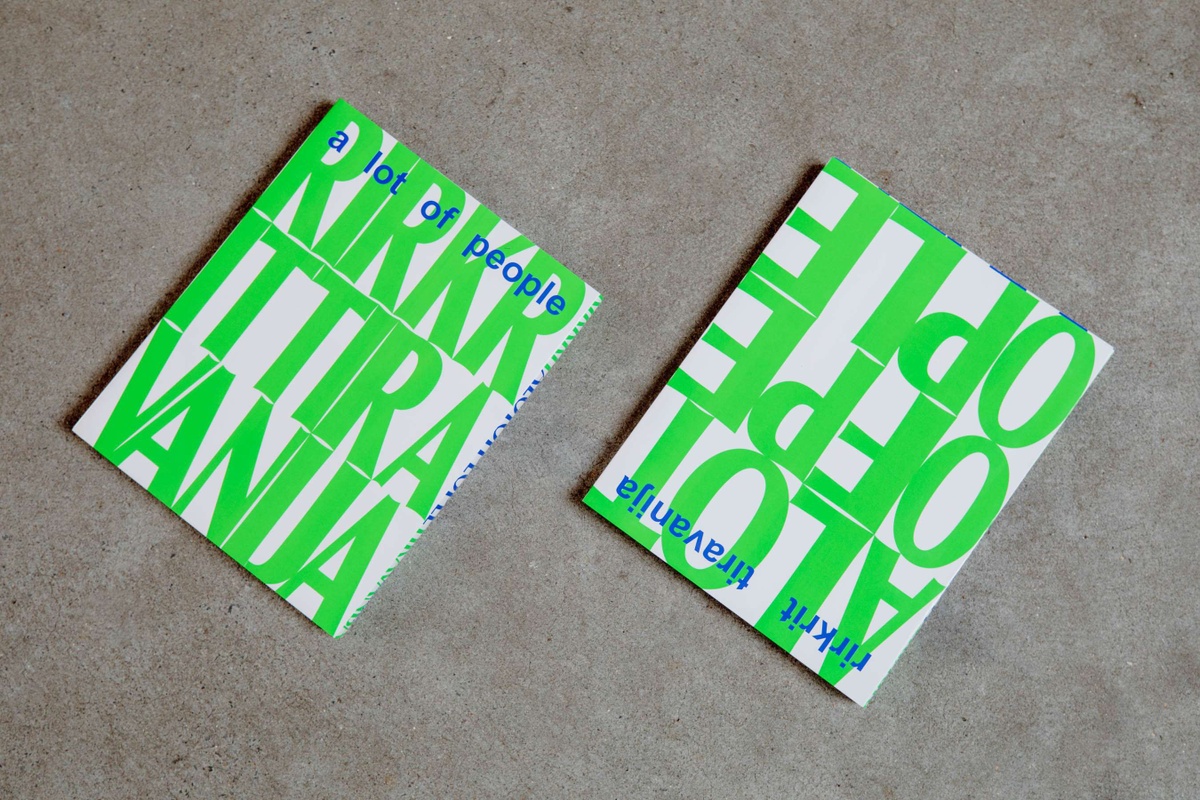

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Oct 12, 2023 – Mar 4, 2024

- Past

- Exhibition

Editing by Marissa Alper. Sound by Nora Rodriguez. Music by David Perlick-Molinari & Paul Hammer, Produced at YouTooCanWoo.

From the start of his practice, a critical material for Rirkrit Tiravanija (Thai, b. 1961) has been the presence of “a lot of people”—a purposefully broad and expansive term that stands as an open invitation to everyone and anyone, present and future. His largest exhibition to date, Rirkrit Tiravanija: A LOT OF PEOPLE traces four decades of the artist’s career and features over 100 works, from early experimentations with installation and film, to works on paper, photographs, ephemera, sculptures, and newly produced “plays” of key participatory pieces. Extending across our second-floor galleries, lobby, and Courtyard, the exhibition includes rarely seen early works that address his experiences as an immigrant with a palpable sense of “otherness” in a Western-centric art world, alongside more recent series that tackle global politics and the quotidian news cycle. Critical to the evolution of recent art in New York City and worldwide, Tiravanija’s interdisciplinary practice has been transnational in scope, engaging notions of cultural difference, interrogating the parameters of place, and negotiating how people can come together.

Central to the exhibition is a newly conceived presentation of five historical interactive pieces, presented on a stage as a series of plays. Tiravanija describes the ongoing evolution of his works: “Like a good recipe, everyone knows what it is, what it tastes like and even how to make it again—perhaps even differently, following their own interpretation; or perhaps it would be a base for something completely different, a possibility.”

Presented on Fridays and Saturdays, the following five plays unfold chronologically over the course of the exhibition. Come back each month to experience a new artwork.

untitled 1990 (pad thai), 1990

October 13 through November 11, 2023untitled 1991/2008 (shall we dance), 1991/2008

November 17 through December 9, 2023untitled 1992-1995 (free/still), 1992/1995/1997/1998/1999/2003/2007/2011–

December 15, 2023 through January 6, 2024untitled 1994 (angst essen seele auf), 1994

January 12 through February 3, 2024untitled 2011 (t-shirt, no t-shirt), 2011

February 9 through March 2, 2024

Dates

October 12, 2023–March 4, 2024

Organized by MoMA PS1, the exhibition also traveled to LUMA Arles (June 1–November 3, 2024).

Location

MoMA PS1

Credits

Rirkrit Tiravanija: A LOT OF PEOPLE is organized by Ruba Katrib, Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, MoMA PS1, and Yasmil Raymond, guest curator, with Jody Graf and Kari Rittenbach, Assistant Curators, MoMA PS1.

Sponsors

Major support for Rirkrit Tiravanija: A LOT OF PEOPLE is provided by Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation, the Family of Lise Stolt-Nielsen, the Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art, and the International Council of The Museum of Modern Art.

Generous support is provided by Glenstone Foundation and Ellen and Michael Ringier.

Additional support is provided by Steven and Alexandra Cohen, Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, and Craig Robins and Jackie Soffer. Funding is also provided by Eileen and Michael Cohen and Laura Steinberg and Bernardo Nadal-Ginard.

Special thanks to Artek and Jungly Restaurant.

Schedule

Tiravanija’s exhibition at MoMA PS1 features many of the artist’s most iconic interactive works. Some are on view daily, while others follow the schedule below.

Key

🍵 A ceremonial tent offers tea and gathering space in untitled 1992 (cure).

🏓 Play ping-pong in untitled 2021 (mañana es la cuestión).

☕ Turkish coffee is served in untitled 1993 (café deutschland).

🎹 Reserve studio time to rehearse or jam in untitled 1996 (rehearsal studio no. 6, open version).

👕 Silkscreen clothing in untitled 2011 (t-shirt, no t-shirt).

Installation Views

Rirkrit Tiravanija. untitled 2017 (fear eats the soul) (white flag). 2017. Flag.

Installation view of Rirkrit Tiravanija: A LOT OF PEOPLE.

Installation view, Lung Neaw Visits His Neighbors. 2011. Digital video (color, sound). 149 min.

Rirkrit Tiravanija. untitled 1998 (cinéma de ville). 1998. Nylon tent with steel zippers, collapsible aluminum and cane poles, acrylic guy lines, plastic hardware, four dual-density foam mats, projector, and DVD player.

Installation view of Rirkrit Tiravanija: A LOT OF PEOPLE.

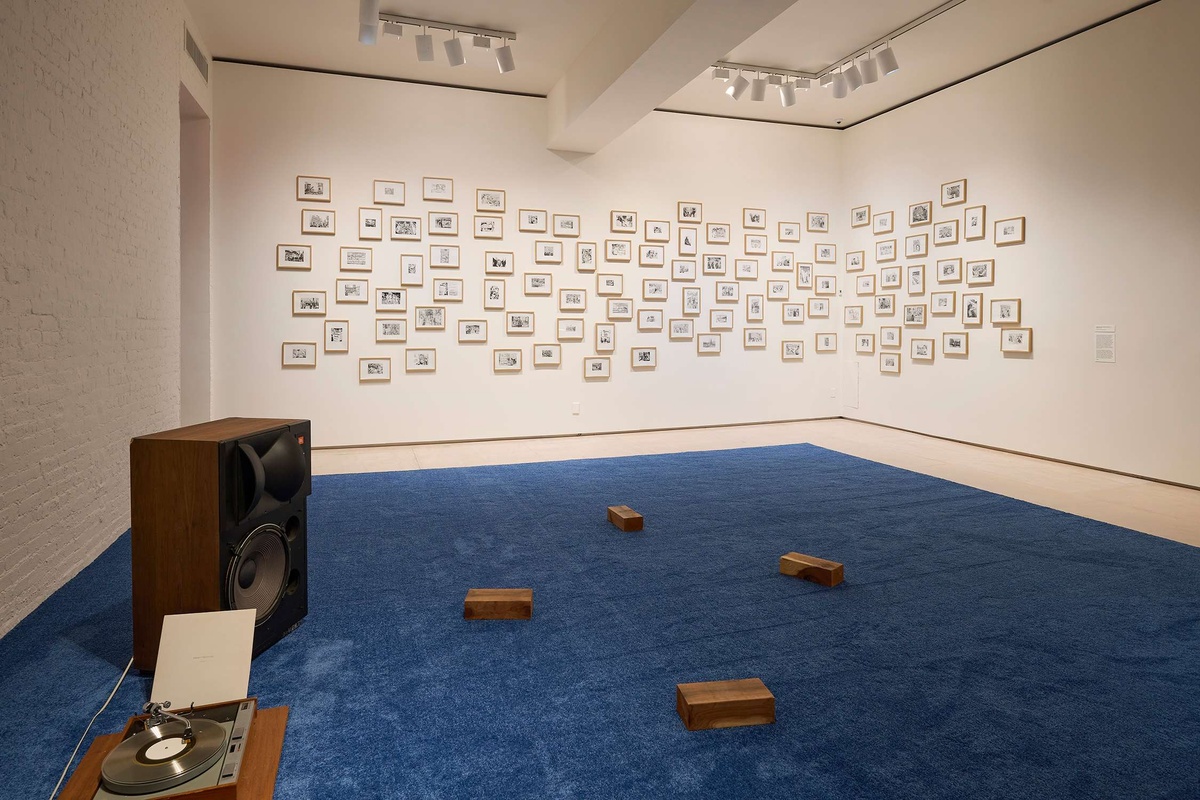

From left: Rirkrit Tiravanija. untitled 2011 (erased rirkrit tiravanija demonstration drawing). 2011. Stereo equipment, blue carpet, wooden Thai pillow blocks, drawings, and vinyl. untitled 2007 (demonstration drawings). 2007. Graphite on paper.

Related Content

Audio

Audio Guide

:

Rirkrit Tiravanija introduces the exhibition.

I think that I would like for the work to be active in making people aware of their positions within the place they’re in, or where they’re standing, or where they’re coming from. I think the work is more of a platform or a stage or maybe sometimes a frame for engagement. So, to use it is to enter into that frame or to step onto that platform. And that stepping onto that platform is a decision, or an awareness of a decision, which I feel has been very important in the work that I’m doing. It is a place to engage.

And in order to be able to give that space for engagement, I’ve always felt that one needs to let things take its course. To let people engage with their own will and interest and whatever brings them to that place. Because I feel that that would maybe produce something none of us would have expected together.

Ruba Katrib: I’m Ruba Katrib and I’m the curator and director of Curatorial Affairs here at MoMA PS1 and I’m a co-curator of the Rirkrit Tiravanija show.

Yasmil Raymond: I’m Yasmil Raymond, Director of the Städelschule and Director of Portikus in Frankfurt, Germany.

Ruba Katrib: This exhibition, marks Tiravanija’s return to the museum. He’s been in several exhibitions here since the early nineties. He’s a critical artist in New York and internationally. He’s exhibited his work in almost every major city in the world that has an art institution. His influence and impact on contemporary art discourses is immense and this exhibition allows us to really look at this expansive practice, bring together works and objects that haven’t been seen since they were initially presented, works that really haven’t been in conversation together in a single exhibition before.

Yasmil Raymond: Those works when they were exhibited, let’s say 20, 30 years ago, they have not been brought back to light. And I think that’s what the exhibition is trying to give a chance for other audiences to younger generation of artists, for example, to be acquainted with his practice, to see how influential he has been, how he changed the definition of art. Not only of art, but also of what does it mean to be an artist. I mean, he’s a maker. Yes, like many artists are. Also, a mentor. He teaches for many years, but also he has been involved in farming, in architecture, and designing, music and occasionally, too, cooking, which is what he became very well known throughout the nineties for known as the cook of the art world. But his roles have been multiple and the way he has championed our understanding of what art can be has been about playing around with these definitions of not only disciplines, but also of activities of what is allowed.

Ruba Katrib: This is a work that takes an exhibition that Rirkrit had staged the gallery many years earlier where he was pairing his own works with Warhol work. So just solidifying that line of influence. So this was held in Gavin Brown’s Soho Gallery location in the nineties, and then when he moved to a larger space in the West Village, Rirkrit rebuilt this gallery to scale. So following the exact floor plan of the gallery, but in plywood. So it has a sort of removed quality and then made replicas of those original works in Chrome. So these works become almost like a memory. A memory and a…

Yasmil Raymond: Material memory.

Ruba Katrib: A material memory that’s then put in a more permanent material. So it’s a way of solidifying and memorializing his own work, his own history, but also these significant spaces that were critical to his own formation as an artist, but also critical to the New York arts community and more broadly. And he is also done this with exact replicas of his apartment in the East Village built in plywood, and he lets other people come in. So I think that’s another interesting aspect that he’s building these spaces and memorializing them, and the ones that are relevant to him personally are then also given over to others to enter and to use and to sort of be inside of and create a new relationship with.

Yasmil Raymond: It’s like he does a warping time because he’s bringing something from the past into the present in a almost scientific science fiction way. All of a sudden, people who were not there like us, we were not at the Gavin Brown Show 1994, but we were able to now experience a sensation or a spirit of that space in today’s version.

Rirkrit Tiravanija: I’ve always felt that to be able to let things go, one needs to be prepared for a lot of different things, a lot of different conditions, a lot of different situations. Also, earlier on, as a young artist, there were situations where, of course, I couldn’t travel because of the person coming from the place I came from and being. So, I would have to just send a fax or send the instruction or send a… It’s much more engaging and beautiful to think of them as scores or recipes, to people to have them make the work.

And I think again, that idea of cooking a recipe, it was always much more interesting to let people take it on themself. And with the understanding, of course, a recipe created in one place could not always be precisely recreated in another place. When I first made Pad Thai, which was very important work, I used a recipe from an American lady who was making a Thai cookbook. And in that cookbook she had the recipe for the Pad Thai. And she used ketchup as a sauce, as a Pad Thai sauce. And it’s, of course, really interesting that she’s able to find a substitute for what we would’ve used in Thailand, which would’ve been tamarind and more ingredients that you can’t find back then. I think the book was maybe written in the late 70s or early 80s. So, for me it was important to think in those terms, also.

I found it to be a practical and useful way of the idea of making art, to just send the recipe and have someone else do it in that way. And I think that we should rethink that much more now so, with the way things are in the world and how we need to rethink about how we use or consume or utilize or travel. And what kinds of resources we do and take up and use to produce something. So, in that way, I think the idea of letting go has been very important in terms of at least the way I make art.

Rirkrit Tiravanija: I come from a culture where, of course, we produce a lot of other people’s things. Like Nike’s factory in the past, or any other number of Western production. So, in our local market, it’s very normal to find reproductions of things.

But what I’m interested in, of course, is models and modeling. And I often speak with Thai artists that, when we make art, we’re engaged in a Western model. We’re not making things that we are, by culture, producing or making, or thinking about making. When we stop painting on the walls of the temple and start to put the imagery onto canvas, we already engage with a completely different kind of cultural production, in that sense. So, for me, I think it’s important to see how, or reflect on use, and think of reusing, because that’s how we’ve engaged with that model, which is the West.

On the other hand, I’m also interested in just using things that already exist. It is a ready-made model, to use Duchamp’s idea, which is that everything is already made. And I wanted to not make more, but to use what’s already made. So, in that sense, the idea of replicating or reusing or remodeling is very important in terms of how I engage with the idea of making art.

Rirkrit Tiravanija: I think I’ve always been an immigrant or itinerant. And, on the one hand, things are more open and receptive and engaging with the periphery, but also on the other hand, there are still a lot of boundaries and barriers and restrictions and things like that.

I mean, I think this idea, to do less or to not make so much and things like that somehow plays into this idea of being an itinerant, because in that sense, one has to move and be present in certain places or certain time and certain spaces in order to engage in the idea of making it.

Because I think that also at the same time, we are starting to realize how the world needs real change or real action or real non-action. And in that sense, I think we really have to rethink everything.

Yasmil Raymond: Photojournalism was his first love. Originally in undergraduate school, he thought for a moment that he wanted to be a photojournalist. So around 2000, he began this practice of collecting archival newspapers and selecting from them images that reproduce photographs, photographs of demonstrations and protests throughout the world. And he takes these images and then gives them to his students or young artists in Thailand that are part of his community. And he’s what we could call his studio, which is a non-studio, and ask them to copy them as works on paper.

Ruba Katrib: Yeah, I think with the demonstration drawings each year that he does this, or each season he’s doing it, or month he’s doing it, you see a different news cycle represented. And he is having students, his studio, others that he is supporting, really their practice as an artist by creating these opportunities in which they can create these drawings and have an income from that. So they have an income from that. But it’s also this sort of idea of displacing and deploying authorship. These images of protests around the world show a sort of collectivity that then also emerges in the methodology of how the drawings are made in which that sort of authorship is distributed.

Yasmil Raymond: This is an early work by Tiravanija, and is emblematic of an important aspect in his practice, which is the ease in which he brings back references to his vernacular Thai culture and his upbringing as a Buddhist. So here you have a reference to a ritual that repeats across Asia and Southeast Asia of a spirit house, cultures that practice animism, but it can be translated also to worldwide, to other cultures that keep altars at the entrance of the house or at a temple. And what I find interesting in this translation from something that you find in the culture that is brought in into the museum as a work of art, is that it gives an introduction to a topic that repeats again and again in his practice, which is the home. You find household products or household appliances in many of his work. So the home and the place of gathering of a family or a community is a big part of his work.

And this spirit house is something that he not only considers a work of art, but is an active object. And it links back to his reaction when he went to school here in the States in Chicago. And he will see these objects that have a functional utility on daily life being put in vitrines in a museum. So in this case, this is a work that lives at his home in Cheng Mai, and that he uses regularly. It works by placing flowers and water and sometimes foods. And it’s something that you find come in everybody’s home. Maybe we can also talk about the issue of translation, right? When you’re coming from another culture. And in his case, what he found early on, and this is a part of a group of works where he was making models and was trying to translate aspect of his culture almost to explain who he was to his peers. In this case, this was a work made in Canada when he was in undergraduate school. And I think this question of displacement of feeling in between or feeling as an outsider is what’s at play here in both the presence of the objects, but also the sign of the letter on the wall. This is the first letter of the Thai alphabet.

Ruba Katrib: Rirkrit is dealing with translation and language and then cultural translation, but also he’s creating a model and it’s a spirit house which is prevalent throughout Thailand. You’ll see them on busy city streets all over the place and they’re cared for, but they’re also a predecessor to his interest in architectural models and really to scale structures that he’s created over the decades of sites that are significant in his own life, but also architecturally significant sites. And this is a really interesting practice of kind of memorializing space. And so while he’s citing a very specific type of architecture that you see in Thailand, it’s also a way of understanding how he’s already thinking about creating spaces and dealing with architecture and how to model that.

Yasmil Raymond: Atlas is an early edition made in photography with photographs that chronicle his travels, but also his interest in history and books that he was reading, or an exhibition that he had just made. So at the same time, it was like a diary, but also giving you an insight of the type of things that were influencing him. And I think this approach he does again and again, whether it is you see it in the large scrolls or in his films where he’s colliding moments of his personal life and introducing that with more abstract or broad views of his context and the people around him.

Ruba Katrib: The Atlas is really interesting because it’s also referencing “Untitled”, Gerhard Richter’s Atlas. So a German artist who created sort of extensive or expansive or endless kind of catalog of images. And this idea of grappling with a sort of encyclopedic approach or how to catalog or capture everything, I think is something that Rirkrit definitely grapples with in these pieces. So he’s not distinguishing the types of materials or images or texts that he’s referencing here. It’s really one guide, one index that puts together all of these different references, memories, personal citations, or historical citations into one piece.

Rirkrit Tiravanija: For me, it was important to find maybe a kind of game or strategy to reengage the work itself into a completely different condition. And that was of course the idea of introducing reenacting. But more, not so much reenacting, because I think, I mean reenactment is interesting. But in a sense, we’re trying to make the thing again, but not the same. And in that sense, the idea of the play or introducing this idea of a staging of a play of the work itself was my solution to maybe the problem I saw in having this exhibition.

And I think that’s maybe the part that I’m interested in terms of the idea of the theater or the performance, is the distance, the distance between the audience and what they’re engaged with, which is maybe the play. And I think that distance, and the positions and the place of which each person stand and watch and sit and look and hear and think is what I’m engaged with, or that’s what I’m interested in. And in that sense, the frame is made for one to be more, at least I hope, aware of their own position, the position that they brought with them when they entered the building or when they got up in the morning and came to see the work.

Rirkrit Tiravanija:

I used to come to PS1 as a young artist to help other artists, actually as a worker, to help other artists from Canada, since I was studying up there and I had some connection with the artists there, so when they came to do an exhibition at PS1, I would be engaged to assist them in the work.

It was a school which I think for me was really, it’s one of those spaces or one of those places you as an artist at that point. It was like going to Nirvana to be engaged with that place, and I’m still interested in those ideas because of course PS1 itself was an alternative to all the other kinds of white cubes and all the other, I would say, very rarefied idea of how artists look at, where I felt like the condition or the kind of ideas behind PS1 was to engage of course with people and to make a place where one could engage and be comfortable and see things that was asking you a lot of questions, so to be back at PS1 was also something that’s important for me in my own journey to become an artist and to be at this place.

Ruba Katrib: Something that Rirkrit said that I think is so key to his work and how he’s thinking about authorship, but also how he approaches making work: he often compares his works to recipes, sort of like an instruction based work that can be taken anywhere and done by anyone. But he also uses this approach with how he quotes artists and art history. He is an artist who has such an extensive knowledge of art history and primarily really the way he engages Western art history I think is very fascinating because as an artist who is from Thailand who lived in different cities around the world growing up, he studied in Chicago at the Art Institute, at the School of the Art Institute attached to the Museum of the Art Institute Chicago, that has an incredible collection. It’s an encyclopedic museum. There he encountered western artists. He encountered the Asian wing in which there were artifacts.

And as he said, he didn’t see any Thai contemporary art on the wall at the time when he was a student there. And I think with works like the series on Philip Guston, where Rirkrit is appropriating Guston’s vocabulary of painting, his references, his motifs, it’s a way of also inserting himself into that history. There’s always an affinity with a lot of his citations. So you feel like there is a real empathy, but then there’s always a bit of a tongue in cheek usurption of that reference and what it means in his hands. And so Guston’s work is very political and as an immigrant also shares some similarities with Rirkrit. But his fascination with these works was this idea of the brick wall that’s reoccurring with these paintings by Guston and this installation, you almost are entering a room that’s surrounded by a brick wall.

And the questions he’s asking about, what is this wall historically, but also what is this wall now? So he takes these references, these historical references, and he deploys them into the present and into the future. So he almost takes them, like he frees them from the original context and in his hands they mean something else. But they also can kind of go on into the future and change, meaning he has done that with references to artists like Jasper Johns, to Rauschenberg, to Warhol, and these run throughout the exhibition. But through his use of appropriation, it’s actually a total recontextualization.

Ruba Katrib: This work by Rirkrit Tiravanija, made in 1998, continues his interest in cinema. He’s an artist who has always worked with film as a medium. We have films in this exhibition that he started making in the eighties. His super eight films are on view in the next gallery. We have more recent films that he’s made, and this pop-up cinema using a tent also harnesses Tiravanija’s interest in being able to basically create an installation. This idea of like a pop-up exhibition, being able to travel lightly and put on a show. And in this particular work, Tiravanija’s historically been interested in documenting cities and thinking about the urban landscape, and basically creating meditations on site in this work in Paris. And he has photographed skateboarders in front of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and then the soon to come Palais de Tokyo on the other side. So this is a really spectacular walkway leading to these art museums. There are stairs, there’s a fountain that is no longer in use. And in the nineties, skateboarders started using this site to do their tricks to hang out. And it’s actually an internationally known skateboarding site. People come from all over the world to skateboard here. And as this is happening in the nineties, and Rirkrit is photographing the skateboarders, so it’s a slideshow versus a moving film, globalized, contemporary art is shifting. and Rirkrit’s a critical part of this evolution of contemporary art.

So as he’s doing this piece in 1998, there’s conversation starting at the Palais de Tokyo as part of this museum complex in terms of turning it into a contemporary arts center and focusing solely on contemporary art. One of the inaugural directors is Nicola Borio, who’s a French curator who wrote a book called Relational Aesthetics in 1998, also in French. And it was later translated into English in 2002. And this became a really critical text in which artists like Rirkrit and a lot of his peers were discussed. When the palate Tokyo opens to the public in 2002, the opening days are very much following a kind of methodology that you can see Tiravanija’s work, where there’s market set up, concerts, DJ sets, different kinds of activities scheduled throughout the day. And so really thinking about how the activity, let’s say, of the skateboarders in this institution basically becomes embraced by the institution and becomes part of the sort of content, but also the context in which they’re working. And so the artists of this generation are really prominently displayed and participating in this institution. And the idea of relational aesthetics, which is this idea that artists are using situations or engagement as a material, is a really critical conversation that emerges in the late nineties and takes us into the new millennium. And of course, there’s critics of this conversation as well, but you can see in this work, this critical turning point of globalized, contemporary art sociability, activities happening on the fringes of the institution, becoming a central part of the institution in this new era of contemporary art. This work, in a way, documents this critical turning point and really how contemporary art comes to be understood.

Ruba Katrib: This is one of the most recent works in the exhibition, untitled 2022 Dark Forest. And this is a piece that references a trilogy of science fiction novels by the writer Liu Cixin. The central theme of this book is basically this idea of this extraterrestrial life that’s out in the universe, and so it’s centered on earth. And so they’re trying to prepare for this impending future in which this hostile takeover of earth is going to take place. So this idea of the dark forest is quite interesting because, when you send a message out into outer space and no one answers, it’s not because they’re not there. It’s because they don’t want to make themselves visible to a potential threat. And so in this work, we have these robotic vacuum cleaners automated that are writing out the Chinese characters for dark forest on this surface. So this is a piece that also relates to many of Tiravanija’s text-based works. And he’s painted text. He’s printed text on t-shirts.

He’s printed text on flags. He’s used slogans throughout his entire body of work. And here it’s being written by vacuum cleaners. So we walk upon it, it gets muddled, it gets erased, it gets remade. So it’s this sort of continuous creation of this text throughout the time that the work is on view. And that sort of ephemeral quality of it, or the fact that it’s sort of barely there, barely registers is really critical to this idea of the dark forest as well. And this work ties into the text-based pieces that you see in this room that come out of this evolution of how Tyra it’s working with text and deploying it, taking it out of context, slightly adjusting the meaning, and then allowing it to project into the future and take on whatever it might take as it’s detached from its original context. And so this work also exemplifies Tiravanija’s interest in new technologies, thinking of new ways of making works and using new means to produce them.

Yasmil Raymond: This work also addresses the topic of utopia, something that is very prevalent in the works. There are text-based works where these messages are open-ended, but they all hint to the promise of a potential successful community, or that together there’s an optimism in Rirkrit’s work that emerges even within the contradictions that he’s wanting always to lead us into thinking of the potential unity of action. And that collective action may lead us out of these issues. So there is, in the critique and in all the work, there’s a critique to society, a reflection, a pondering on the issues that are important of great importance today, but they often unfold as well with a optimistic message or an open-ended invitation for us to form alliances and solve them together through action.