Life Between Buildings; Or, What Might Grow Where You Least Expect It

- Writing

Life Between Buildings; Or, What Might Grow Where You Least Expect It

…trying to go

to helpful keepers of the knowledge try to go

to the place in the mud that is where I try to live

in peace great mud of this great kissing loving

earth…

– Hannah Emerson, “Becoming Mud”

In 1649, a British man named Gerrard Winstanley led a group of fellow peasants on an illicit mission to sow peas, carrots, and corn in the commons of a town in Surrey, England. Calling themselves the Diggers, the group asserted that the use of land for subsistence was an inviolable right and urged others to join them in farming leftover scraps of land—the banks of roads, open fields, marshlands, common greens. Proto-communist in their thinking, the actions of the Diggers stand as an early example of “guerrilla gardening”—the greening and tending of land that one does not technically own. “Mine and Thine shall be swallowed up,” Winstanley posited in a manifesto of the Diggers, asking “whether the Common people shall have the quiet enjoyment of the Commons and the Waste Land, or whether they shall be under the will of Lords of Mannors still.” 1 At this moment in British history, “commons” and “wastelands” were under a specific threat: governments and wealthy individuals were increasingly expropriating liminal lands that had for generations been accessible to all (for grazing, foraging, or gathering wood) for private use, enclosing them with fences, hedges, or ditches. 2 The Diggers’ efforts did not stop the tide of enclosure, and a similar wave of privatization took off in the United States, where settlers, under the banner of Manifest Destiny, claimed land long stewarded by Native people. Yet the Diggers established an early and impactful precedent for thinking about the “Earth [as] a Common Treasury for All, both Rich and Poor.”3

From the very birth of private property, struggles over use and need, on the one hand, and ownership and profit, on the other, have come to a head in interstitial or “leftover” spaces: the scrap, in other words, can be key to rethinking the whole. Life Between Buildings takes such terrains vagues as its point of departure, 4 (footnote “The term terrain vagues, coined in 1995 by architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales, refers to “seemingly abandoned or overgrown sites—where the landscape has gone to seed and been left to its own devices, is in suspended redevelopment, or is being furtively inhabited or otherwise used, under the radar of local authorities…” See Manuela Mariani and Patrick Barron, eds., Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale (New York: Routledge, 2014), 1.”) exploring the entangled history of artists and community groups from the 1970s on as they sought to engage, document, garden, and reinvigorate the interstitial spaces of New York City—its “vacant” lots, sidewalk cracks, traffic islands, parks, and others. 5 The artists and community groups featured in the exhibition at MoMA PS1 and discussed in this essay teach us how one sliver of land—a community garden, a strip of weedy grass, a triangle of pavement—can encapsulate and refract the shifting politics of space in a city such as New York.

*

In the late 1960s, some three hundred years after the Diggers’ agitations, groups across the United States began to resuscitate their ideas, positing land as something to be held and cared for in common. “Back to the land” movements proliferated. A group in San Francisco went so far as to adopt the name The Diggers, using street theater and direct action to advocate for the abolishing of private property. 6 Around the same time, on the opposite coast, a group of Puerto Rican and Nuyorican youth in the Lower East Side and El Barrio (East Harlem) formed a group called The Real Great Society, which in 1968 became known as CHARAS, an acronym for the first letters of each of their names. 7 Influenced by the radical actions of the Young Lords and the Black Panthers, they responded to the government’s acute neglect of their communities by establishing programs fostering self-determination and mutual aid.

One main goal for CHARAS was to address the lack of quality housing in their neighborhoods and re-energize neglected urban spaces. In 1968, they invited the polymath Buckminster Fuller—most famous for inventing the geodesic domes that were dotting utopian communes across the country—to speak at the University of the Street, a free school established by CHARAS in an empty storefront on Tompkins Square Park in the Lower East Side. 8 Inspired by the modularity and DIY ethos of Fuller’s structures, CHARAS began constructing geodesic domes in empty lots around the Lower East Side, envisioning them as gathering spaces, housing, and test-runs for potential communities in upstate New York or Puerto Rico. 9 The cover of Dome Land!, a comic published by the group in 1974, depicts members piled into a car headed toward a dome nestled in the woods at the edge of a sandy beach—an amalgamation, perhaps, of upstate New York and Puerto Rico—with the Twin Towers and Empire State Building receding in the distance. Before this dream of a “Dome Land” in nature could come to fruition (an exodus that, in fact, never happened), they began erecting these structures—laden with cultural symbolism of rural communes and flower children—among the rubbled lots of the Lower East Side. In 1972, they built one such dome on Jefferson and South Streets, in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge—filling one of the city’s many “empty” spaces with the possibility of common life.

A year prior and a couple blocks to the south, a young curator named Alanna Heiss had organized a sprawling outdoor exhibition at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, the first of many projects Heiss staged in underused city buildings and unexpected venues under the banner of the Institute for Art and Urban Resources. Foundational to the “alternative space” movement, she went on to found PS1 in 1976 in a decommissioned school building in Queens. But for The Brooklyn Bridge Event, as it was called, Heiss was looking outside of buildings. She invited a group of artists to create site-specific pieces responding to the architecture of the Brooklyn Bridge and the largely barren areas around it. Located outdoors, ephemeral, and often performative in nature, the works infiltrated the nooks and crannies of this borrowed space, challenging the very precepts of exhibition-making. Gordon Matta-Clark, fresh out of architecture school at Cornell, contributed three projects. Struck by the ingenuity of an improvised dwelling designed by an unhoused man living near the foot of the bridge, Matta-Clark piled up junked cars left abandoned at the site, hoisting them up to create a sturdy, if makeshift, shelter and calling the work Jacks (1971). 10 Garbage Wall (1971) also repurposed detritus toward architectural ends by encasing trash and empty cans collected from the area in metal mesh. The result was a prototype for modular walls that could be constructed cheaply from the detritus of urban life. At the debut of the exhibition, Matta-Clark orchestrated Pig Roast, which was just as it sounds: a pig, roasted on a spit, from which he made sandwiches handed out to art world attendees, and those that had gathered to see what on earth was going on. 11

Matta-Clark and CHARAS—as well as Heiss—hailed from wildly divergent backgrounds and approached their practices with very different stakes, but they all grappled critically with the particular spatial conditions of New York City in the early 1970s. Each saw new possibilities in the “negative” spaces of the city, rethinking how housing could be constructed, what an exhibition could look like, and what stewardship rather than ownership might mean. Though perhaps unknown to each other at this time, these projects—occurring in such quick succession, in the shadow of neighboring bridges—inaugurated for both Matta-Clark and CHARAS an abiding interest in what might emerge from the spaces between buildings. In 1976, their paths would cross again in a vacant lot on East 9th Street and Avenue C, on the cusp of its flowering into a garden. Such convergences, parallels, and missed connections guide Life Between Buildings in its effort to trace a few of the many stories—the interwoven roots—that comprise this history.

*

That artists and community groups were turning to such spaces in the 1970s is unsurprising considering the spatial and economic conditions of New York City at the time. The “empty" spaces that CHARAS and Matta-Clark engaged were among many lots and derelict buildings dotting the Bronx and neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side and Bushwick—predominantly working-class neighborhoods home to large communities of people of color. Such spaces were symptomatic of, and bound up in, a municipal fiscal crisis that reached its boiling point in 1975, when the city approached bankruptcy. New York City had lost approximately five hundred thousand manufacturing jobs in the preceding decade; a large portion of the middle-class population simultaneously decamped to the suburbs in a process known as “white flight”; and the city became increasingly divided along racial lines as a result of redlining and the segregated placement of public housing. Property lost value and public debt skyrocketed, spurred in part by a city-backed boom in office construction (as with the World Trade Center, which was unveiled in 1973). 12 Many landlords abandoned buildings as the cost of upkeep exceeded property values. In some cases, landlords burned buildings down to collect insurance money, displacing their tenants in the process. “There it is, ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning,” journalist Howard Cosell declared glibly on air during a 1977 Yankees game, as the aerial camera panned across a school building, blocks from the stadium, engulfed in flames. 13

The landscape that resulted from such disinvestment has often been referred to as “empty,” “vacant,” “abandoned,” or “blighted.” On some level, these words accurately describe the proliferation of lots devoid of buildings and piled with refuse. But to call a neighborhood empty overlooks the residents that still live there, the communities of unhoused people that creatively reuse these open spaces, and the nonhuman forms of life that take root. If you can see a neighborhood as truly empty, it becomes easy to erase it mentally and, sometimes, physically. Banker Felix Rohatyn (who helped negotiate the terms by which New York avoided bankruptcy, involving extreme austerity measures that slashed public spending) suggested, for example, that the best way to deal with a “blighted” neighborhood was to “clear it, blacktop it, and develop an industrial park with the whole package of tax, employment, and financing incentives already in place.” 14 The urban renewal policies of the immediate postwar era, which leveled whole neighborhoods with the promise of improvement, had leveraged rhetoric of “cleaning” neighborhoods that were too crowded and too poor. In the 1970s, it was the supposed absence of life that both rationalized neglect and attracted the promise of future development.

Members of the communities actually living in such neighborhoods had other ideas about what to do with these spaces. As architect and historian Nandini Bagchee has written, “During periods of crisis, when property is suddenly devalued, its status as ‘real estate’ is overturned. Crisis returns property, land, and the built environment back to the question of use and potentially back in the hands of its users.” 15 One key way in which these lots were being returned “to the question of use” was through the efforts of community gardeners, who looked at rubbled lots abandoned by landlords and saw the possibility for verdant gardens that could feed, educate, and unite their communities. Driven by rising food costs due to inflation, increased environmental awareness (the first Earth Day occurred on April 20, 1970), and receding government oversight and aid, the greening of such open spaces became part of a radical effort to reclaim space for community use. 16

Though repopularized in the early 1970s, organized communal urban gardening in fact traces back to the 1890s. In cities like New York, Detroit, and Philadelphia, “vacant-lot cultivation associations” popularized by social reformers and proponents of the “city beautiful” movement turned undeveloped land over to impoverished residents to cultivate. In New York City, 138 acres (1,656 city lots) in Long Island City were transformed into urban garden plots. 17 During WWI and WWII, the government promoted urban gardening as a patriotic duty. 18 Moralizing overtones accompanied such efforts: gardening was seen as a means of improving not only spaces but people. As historian Laura J. Lawson has written, reformers sought to “link idle land with idle hands to satisfy intertwined impulses for education and beautification,” positing gardening as a means of “self-help” that would counter perceived laziness and prepare participants for homeownership outside of the city. 19 Such notions still haunt discourses around community gardening, even as many gardeners fought (and continue to fight) against the prejudices engrained in those very terms. Rather than subscribe to top-down directives of what “beautification” or “improvement” might mean, the gardeners who took up the mantle of urban gardening in the 1970s often did so under the banner of self-determination. For who is to judge what improvement looks like, or what needs improving in the first place?

A black-and-white photograph by Marlis Momber from the early 1980s depicts an expanse of 4th Street between Avenues C and D in the Lower East Side razed to the bare ground. Across the street, a half-demolished tenement crumbles under the weight of its structure. 20 “War” and “frontier” metaphors proliferate in narratives around the Lower East Side in the 1970s and early 1980s, and one might momentarily see this as an image of a bombed-out Berlin. 21 But look closely and you will recognize a circle of raised garden beds—the very beginnings of El Jardin del Paraiso, which remains an active community garden today. Other groups and activists had spearheaded such efforts in the decade prior. In 1970, Hattie Carthan, a resident of Bed-Stuy, launched a fight to save a magnolia tree on Lafayette Avenue, which led to the founding of the Magnolia Tree Earth Center and community garden in 1980. “I adopted that tree when I moved to Brooklyn,” she stated. “I wasn’t about to let it die. Brooklyn has already lost too many trees and houses and people.” 22

Puerto Rican and Nuyorican residents of the Lower East Side (or Loisaida—a name introduced by poet Bimbo Rivas in 1974) began gardening in the 1960s and early 1970s, often creating gardens centered around elevated wooden shelters known as “casitas” that harken back to vernacular architectures of Puerto Rico (traced, even, to Taíno designs). 23 These “casita gardens,” as scholar Miranda J. Martinez has written, “reproduce a way of life that anchors the Puerto Rican community on the Lower East Side.” 24 Such gardens, along with simultaneous homesteading movements, would become important forces in the development of Nuyorican culture and art in the Lower East Side. Other artists, who had moved to the neighborhood in search of cheap rents, also began transforming “wasted” lots into gardens. In 1973, artist Liz Christy organized a group called the Green Guerillas, with the aim of greening the neglected landscape of Lower Manhattan by seed- bombing vacant lots. 25 “It was a form of civil disobedience,” states Amos Taylor, who was an early member. “We were basically saying to the government, if you won’t do it, we will.” 26

In 1973, Christy and fellow members started the Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden at the intersection of the garden’s titular streets; it is now credited as the first community garden in the Lower East Side. 27 (A 1975 photograph shows members of CHARAS gathered in front of a geodesic dome they built at the garden—evidence of the interwoven nature of these related approaches to recycling urban space). But not everyone was pleased with such gardening efforts. In a local newsletter that Christy helped start, a neighborhood child wrote in critically: “Let’s get one thing straight. We’re just as much a part of this neighborhood as you are… . The cops must be sick and tired of getting calls from you hippies… . One more thing: you didn’t think of us when you put the trees up and now it’s difficult for us to play football and stickball.” 28 Such conflicts were not uncommon; as space became available, schisms arose around how exactly to use it. What looks like improvement to some is experienced as cooptation by others. 29

*

Though the role of artists in gardens has been contentious at times, the early 1970s saw many artists in New York incorporating an attention to the city’s ecology—environmental, social, and architectural—into their practices. Some artists were directly involved in gardening, especially in the Lower East Side, where they joined squatters, anarchists, community organizers, and Puerto Rican residents to reclaim lots and transform them into gardens that became vibrant spaces for art and performance. 30 Others made artworks influenced by the ways in which gardeners reclaimed overlooked and liminal spaces in the city. For many, the politics of urban space itself became a medium.

In 1971, the same year that Matta-Clark participated in the Brooklyn Bridge Event, he made a series of drawings titled Tree Forms. Calligraphic lines trace entwined tree limbs and meandering floral vines, which seem to double as shelters. Some of the drawings were blueprints for “hit-and-run gardens” he dreamed of planting overnight in undeveloped lots, specifically in the South Bronx, anticipating his subsequent interest in the voids between buildings and pockets of unbuilt space. 31 In 1973, Alanna Heiss introduced Matta-Clark to New York City municipal auctions in which bidders could purchase “sliver lots,” oddly shaped lots as small as one foot by one foot that the city hoped to get back on the tax rolls. 32 Matta-Clark acquired fifteen lots for between $25 to $75 each. Fourteen of these Fake Estates, as he called them, were located in Queens. In the early twentieth century, Queens had rapidly transformed from farmland to city, and the process of imposing urban street plans atop rural property lines resulted in these minute, leftover lots, as did surveying errors. 33 Matta-Clark was interested in these “gutterspaces” precisely because they were often inaccessible, weed-ridden, and “useless” for development. “What I basically wanted to do,” he stated, “was to designate spaces that wouldn’t be seen and certainly not occupied. Buying them was my own take on the strangeness of existing property demarcation lines. Property is so all-pervasive. Everyone’s notion of ownership is determined by the use factor.” 34 In Fake Estates, “Jamaica Curb,” Block 10142, Lot 15 (1974), black-and-white photographs track the entirety of the 3-foot-by-230-foot lot purchased by Matta-Clark—a strip of grassy curb turned “private” garden that anyone could walk on, a parody of the absurdities of ownership.

A 1975 trip to Milan, during which Matta-Clark collaborated with young anarchists squatting an abandoned factory, inspired his desire to work more closely with grassroots initiatives. 35 He sought to make his work “not in artistic isolation, but through an active exchange with peoples’ concern for their own neighborhood,” going on to state: “My goal is to extend the Milan experience to the US, especially to neglected areas of New York such as the South Bronx where the city is just waiting for the social and physical condition to deteriorate to such a point that the borough can redevelop the whole areas into the industrial park they really want.” 36 (Cue Felix Rohatyn.) Shortly thereafter, he proposed A Resource Center and Environmental Youth Program for Loisaida, which would teach Lower East Side youth the skills to homestead abandoned buildings and turn lots into gardens—activities, as he was well aware, already prevalent in the neighborhood. This work, he wrote, “would no longer be concerned with just personal or metaphoric treatment of the site, but finally responsive to the express will of its occupants.” 37 A preliminary facet of the project involved working with CHARAS to construct an amphitheater out of railroad ties in a lot at East 9th Street and Avenue C that was being turned into a community space. 38 Photos by Matta-Clark taken circa 1977 show this early collaborative work, the armature of a geodesic dome visible in the background. Matta-Clark passed away in 1978, before he could see the space become a flourishing garden— now known as La Plaza Cultural de Armando Perez.

Like Matta-Clark, Chilean-born artist Cecilia Vicuña was also drawn to the interstices of the city. Exiled from Chile following the US-backed overthrow of Salvador Allende’s government in 1973, she moved to New York in 1980 and began wandering the riverside, streets, and vacant lots of Tribeca. Among their cracks and crevices, she created small, site-specific performance installations she called Sidewalk Forests (1981). An eco-feminist avant la lettre, Vicuña had been creating ephemeral installations since the 1960s that, in their fragility, recalled the intertwined fates of the earth and humanity. In her Sidewalk Forests, she turned her attention to the weeds bursting through the cracks in the city pavement, highlighting them with bits of thread and dashes of chalk. “I immediately connected in New York with what is invisible to New Yorkers. First, the cracks in the sidewalk … I’m engaging them as a connection to the future return of the city to the forest or to the nation’s past when this was Lenni Lenape territory.” 39 For Vicuña, a single weed can challenge New York’s teleological narrative of development by making visible an Indigenous past and potential future. Not long after making this work, Vicuña became a member of a community garden founded in an undeveloped lot in Tribeca, where she still cares for a plot today.

In 1977, just a few blocks from where Vicuña would create her Sidewalk Forests, artist Becky Howland turned her attention to a traffic island bounded by Franklin Street, Varick Street, and West Broadway. Unkempt grass grew long and wild on the small triangle of pavement, which Howland bent and tied into undulating waves—a precise homage to unruliness. Photos show the installation as a shock of green against a deserted concrete landscape. Tied Grass (1977) was one of several quiet interventions Howland made into the cityscape around her basement studio in Tribeca. After making Tied Grass, she turned her attention to another nearby traffic island, located at the intersection of Canal Street, Sixth Avenue, and West Broadway, and home to a gas station whose wedge-shaped footprint echoed that of the concrete island it sat on. She installed a small geometric replica of the gas station at the “prow” of the triangular island. A monument in miniature, Portrait of a Gas Station (1978–c.1998) played on shifts in scale, from model to traffic island to the island of Manhattan. Howland replaced the original plaster version with a concrete one that remained there for nearly two decades, surreptitiously embedded into the sidewalk with the help of filmmaker Charlie Ahearn. Like Vicuña, Howland’s guerrilla-style interventions drew subtle attention to the oft- forgotten materiality of Manhattan—the sheer fact of its islandness.

Howland would eventually move into her Tribeca basement studio, but at this time in the late 1970s she lived in the Lower East Side. Her commute to and from the studio took her past one of the largest gardens at the time, Adam Purple’s “Garden of Eden,” which grew across five lots on Eldridge Street in the shape of concentric circles with a yin-yang symbol at its center. In a collaged drawing from 1979, Howland captures its green growth amid devastated buildings left to crumble by their owners. For her, the garden symbolized hope. It was bulldozed in 1986 by the city to make way for public housing, becoming a lightning rod for debates over whether gardens should be developed for housing. Government officials often pitted gardens and housing against each other, forcing constituents with shared concerns to fight over the same scraps of land—even when, as many pointed out, there were often plenty of vacant lots without gardens available for development, too. In the case of the Garden of Eden, numerous architects submitted plans showing how both the housing project and the garden could coexist. 40

Around the same time, Howland became involved with Collaborative Projects Inc., aka Colab, a collective interested in exhibiting art in public and nontraditional spaces. She was a key organizer of the now-legendary Real Estate Show, orchestrated in protest of real estate speculation and dedicated to Elizabeth Mangum, who was killed while resisting eviction from her Brooklyn home. The group broke into an unused city-owned building on Delancey Street to mount the exhibition. It was open for one day—January 1, 1980—before the city padlocked the doors. When the city shut it down, Howland helped negotiate access to the storefront of a city-owned tenement building on Rivington Street, which became the alternative art and music venue ABC No Rio, legendary in the punk and hardcore scenes. Howland cleared a pile of bricks and rubble from the backyard and built a large-scale fountain called Brainwash (1981–83) among the ailanthus trees growing there. When ABC No Rio shut down in 2016 for demolition, Howland returned to preserve the trunk of her favorite ailanthus tree. 41

In 1983, Colab turned the reins of ABC No Rio over to Peter Cramer and Jack Waters— dancers, key figures in the downtown queer performance scene, and partners in art and life. They started their tenure with a raucous, 24/7 weeklong affair called The Seven Days of Creation. The backyard was a source of inspiration for them, as it had been for Howland, and they organized performances and dinners in the backyard area around Howland’s sculpture, calling their venue the Fountain Cafe. Acutely aware of the social and class divides between the mostly white artists who gathered at ABC No Rio and the largely Puerto Rican locals, they sought to engage their neighbors, even starting an educational program at nearby public schools. As Cramer notes, they asked themselves: “What are artists really doing in these neighborhoods, and what is the effect of that?”42

An investigation into the “effect” of artists in urban space was core to their practice. From 1981–85, they convened a performance collective called POOL (Performance On One Leg) with Christa Gamper and Brian Taylor. POOL’s often-shifting participants explored how sexuality, race, class, and urban ecology intersect. In addition to shows at ABC No Rio and the Pyramid Club, POOL frequently performed in public and semi-public spaces such as parks, pools, streets, and construction sites. Like each of the artists discussed thus far, POOL used the city as a stage out of economic necessity. But they also were keen to challenge ideas of propriety, testing the limits of public space and exploring ancient rituals of communion with the seasons and environment. An early performance titled POOL at the Pool took place at Hamilton Fish, a public pool in the Lower East Side dating to the Robert Moses era. (“You may have to climb a fence,” read the event flyer). They performed an aquatic routine that culminated with the ritualistic burning of a banner at dusk. Video documentation captures neighborhood youth watching with perplexed fascination, amicably teasing the performers. According to Waters and Cramer, these children became frequent audience members at their impromptu performances.

On July 31, 1983, POOL staged multiple performances on a stretch of sandy landfill downtown. 43 Members danced Trench!/Fractured White (choreographed by Gamper) atop steep bluffs of landfill, dwarfed by the World Trade Center towering just behind them. Images of the performance capture a city on the brink of change: The AIDS crisis was escalating. Reaganism was taking hold as the city recovered from a recession. 44 New buildings rose in lots formerly abandoned by landlords, class divides were sharpening, and space becoming increasingly monitored. Soon, the rugged expanse upon which they danced would be replaced by the gleaming development of Battery Park City. Nevertheless, Cramer and Waters continued to find pockets of wildness in the city. In 1996, they turned a lot on East 2nd Street into a community garden called Le Petit Versailles, which remains an active space for queer gathering, experimental art, and community organizing even as the Lower East Side has changed drastically around it.

*

Community gardens continued to grow in number throughout the 1980s, against the backdrop of a city in flux. As sociologists Manuel Castells and John Mollenkopf write, “Between 1977 and the stock market crash of October 1987, New York sustained an unprecedented economic boom, with median household income rising about 20 percent in real terms as a result of the prosperity.” 45 This wealth was unevenly distributed: poverty rates increased even as top earners made more. Empty lots once again seemed like a profitable investment. Gentrification escalated, especially in neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side, as did homelessness. In 1986, the city ceased its homesteading program, which had allowed residents to gain ownership of city-owned properties through sweat equity. 46 The threat of development loomed large over community gardens. Between 1980 and 1983 alone, about 10 percent of gardens in Manhattan were sold for development. 47

A series of photographs made between 1989 and 1993 by Margaret Morton, a longtime resident of the Lower East Side and a professor at Cooper Union, capture this constellation of forces as they unfolded in the gardens of her neighborhood. In the late 1980s, Morton began documenting unhoused people who built improvised dwellings in Tompkins Square Park. When the city evicted the park’s residents in 1991, Morton continued to befriend, photograph, and interview them as they dispersed to nearby lots. 48 She became particularly interested in the gardens they established there. Often temporary, composed of found materials, and growing in harsh conditions, she saw them as challenging conventional understanding of gardens as “the domain of settled or prosperous individuals only” and began documenting them alongside the larger ecosystem of gardens in the area. 49 In Jimmy’s Garden (1989–93), Morton captures a local unhoused man relaxing next to a goldfish pond he had built and filled from a nearby fire hydrant. The city bulldozed his garden a week after Morton took this photograph. Once they razed gardens like Jimmy’s, the city sometimes turned the lots over to “official” community gardens. For example, Eighth Street Garden, also documented by Morton, was planted on a lot from which people had been evicted. Morton notes, “There were complaints from homeless people, including Pixie, who had been thrown off the lot. The city, they said, cared more for plants than for people.” 50 Gardens served as forms of empowerment but also, sometimes, agents of displacement and “greenwashing”—a dynamic that continues today, as community gardens become handy marketing tools for developers.

Mel Chin, known for large-scale ecological art projects, was also paying attention to the turbulent politics of public space in the late 1980s as they intersected with fraught notions of “beautification.” Like Howland a decade before, Chin made a series of works focused on one of the many triangles of land resulting from urban renewal projects that drove large streets and infrastructure projects through the city’s grid—in this case, the Manhattan Bridge. In a series of drawings submitted for the 1988 exhibition Public Art in Chinatown at the Asian American Arts Centre, Chin proposed to adapt a small triangle of land at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge into a community park. His design arose from conversations with an elderly Chinese man who lived in a labyrinthine shelter on the site, as well as other Chinese-speaking members of the neighborhood. Chin decided to use the practice of feng shui to transmute the parcel into a landscape culturally legible to the Chinatown community. 51 The resulting design took the shape of an oyster, a species native to New York City’s precolonial landscape and used in Chinese alchemy. Sketches for his plans show the “pearl” of the oyster marking the site where debris of the existing shelter would be ceremonially buried, paying respect to the one who lived there. As Chin developed his proposal, the triangle, known as The Hill, became home to a larger community of unhoused people (whom Morton would go on to photograph) and he became increasingly invested in drawing attention to their need for housing. 52 Chin’s plan was never realized, and The Hill was forcibly bulldozed by the city in 1993, displacing those that lived there. In 2016, the city turned it into an official park marketed as “Chinatown’s mini High Line.”

The taming of public space and the monitoring of its users’ behavior became a key subject for artist Tom Burr in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He began looking closely at parks and public restrooms—sites that were, in his words, “illustrative both of disappearing public realms as we had come to know them, but also of gay male signification.” 53 Burr spent hours wandering Central Park and Prospect Park, both designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in the nineteenth century, noting the ways in which people occupied these spaces against the grain of their state-sanctioned uses. In a 1992 show at White Columns, Burr focused on the Ramble, a wooded area of winding paths nestled within Central Park, which Frederick Law Olmstead had planted as a “wild garden,” dense with foliage approximating his idea of an “indigenous” landscape. 54 This lured migratory birds, which in turn attracted bird-watchers. The secluded area has also served as a cruising ground for queer men since the early twentieth century. The first of these unintended uses became a point of pride for the park, with bird-watching celebrated in brochures Burr collected from the park’s main office; the second was unmentioned and policed. Burr made miniature replicas of the Ramble using model- making materials, highlighting, in their perfectionism, the artificial nature of the seemingly “wild” landscape. Yet he also included the unplanned paths worn into the landscape over time by gay men cruising: known as “desire lines,” these paths reveal how public spaces can double as zones of autonomy. Covertly etched into the landscape, the paths counter a mandate of “preservation” that can double as a form of control. 55

The mounting pressures that Morton, Chin, and Burr responded to in their works only escalated throughout the 1990s. 56 When Rudolph Giuliani became mayor in 1994, he began selling community gardens to private developers, part of a larger pro-development agenda that concomitantly criminalized the poor and unhoused. It culminated in a public auction planned for 1999 in which over one hundred gardens would be sold to the highest bidder for unrestricted use. Community gardeners and activists across the city rose to their defense, but were met with derision: “This is a free market economy. Welcome to the era after communism,” Giuliani is purported to have said. 57 Despite his flippancy, the New York Supreme Court halted the auction at the last minute, concluding that the city had failed to prove there would not be environmental harm. 58 Nonetheless, many gardens were bulldozed. A multimedia installation by Aki Onda titled Silence Prevails: Lower East Side Community Gardens During the Pandemic (2020/2022) traces the complexity of these struggles through historical documents and photographs, paired with recent audio recordings and images captured in gardens during the early days of the COVID-19 closures. A photograph from 2000 shows protesters resisting the bulldozing of El Jardin de Esperanza, some of whom camped out in a treehouse the shape of a coquí frog, a symbol of Puerto Rican resistance. The garden was bulldozed on February 15, 2000, the same day that the court’s injunction went into effect. The destruction galvanized ire: a flier exhibited nearby in Onda’s installation takes the form of a “wanted” poster. Its target: Donald Capoccia, the developer who bought the land beneath the garden, bulldozed it, and proceeded to build an apartment building called, ironically, “Eastville Gardens.”

*

Today, there are approximately 550 community gardens across the five boroughs, accounting for about one hundred acres of open space. 59 By and large, they are protected from development through city policy and public sentiment, though struggles persist. 60 If community gardens symbolized a glut of “empty” space in the 1970s, they now nod, through the sheer surprise of their existence, to its extreme lack. Artists like Matta-Clark and Vicuña saw the gaps and fissures of the cityscape as portals to expansive and radical thinking. At the same time, these interstitial spaces presaged the kind of spatial squeeze that exists today—a pervasive condition for many young artists, and one that impacts and informs their work. 61

A sliver lot in 2022, for example, connotes something very different than it did in 1973, when Matta-Clark made his Fake Estates. 62 Many have been swallowed up by neighboring properties, but they do still exist. Niloufar Emamifar’s Ocean Avenue (2022) focuses on lot 74, block 6739, on Ocean Avenue in Brooklyn. The lot is six inches wide and seventy-one feet long and was purchased in 1954 at municipal auction by a real estate developer who lived across the street. He bought it “on a lark” for twenty-five dollars. As of February 2022, his descendants owe $1,998.49 in taxes and the lot is pending foreclosure. 63 Sandwiched between a private Jewish school and a kosher restaurant, the lot was hidden behind a six-inch-wide wooden plank, which Emamifar removed to reveal a narrow slit of air between the two buildings. Likely among the world’s narrowest fences, the single plank points to a recurrent theme in the history traced here: as much as gardens are about nature, they are also about property lines, and how those lines are made visible, enforced, or concealed. Attention to these boundaries and how to break them suffuses the works of a younger generation of artists in Life Between Buildings.

David L. Johnson’s Adverse Possessions (2022–ongoing) reminds us that many spaces in New York City that appear public are in fact privately owned. Johnson makes work inspired by frequent walks throughout New York City, observing and documenting moments in which typically invisible structures of power gain legibility. Adverse Possessions comprises a number of metal plaques that the artist dislodged from sidewalks and “public” plazas around buildings in Midtown Manhattan and the Financial District, where they are used to mark the edge of private property. Colloquially known as “squatter’s rights,” adverse possession is a legal concept with origins in English common law of the Middle Ages that allows someone to gain legal title to land if they have demonstrated continuous occupation of that land for a set period of time—in New York State, ten years. Community gardens have used the concept to counter threats of development, 64 but adverse possession is difficult to claim: one must meet specific criteria, including that one’s occupation of land is “hostile” (against the permission of the owner) and “open and notorious” (commonly known to the owner and others). By visually declaring their ownership through plaques, building owners grant tacit permission to anyone who crosses their property line, thereby negating potential claims of adverse possession. 65 Johnson’s ongoing removal of plaques opens these spaces to other forms of activity and stewardship: a proverbial leveling of the invisible fences that choreograph our access to space.

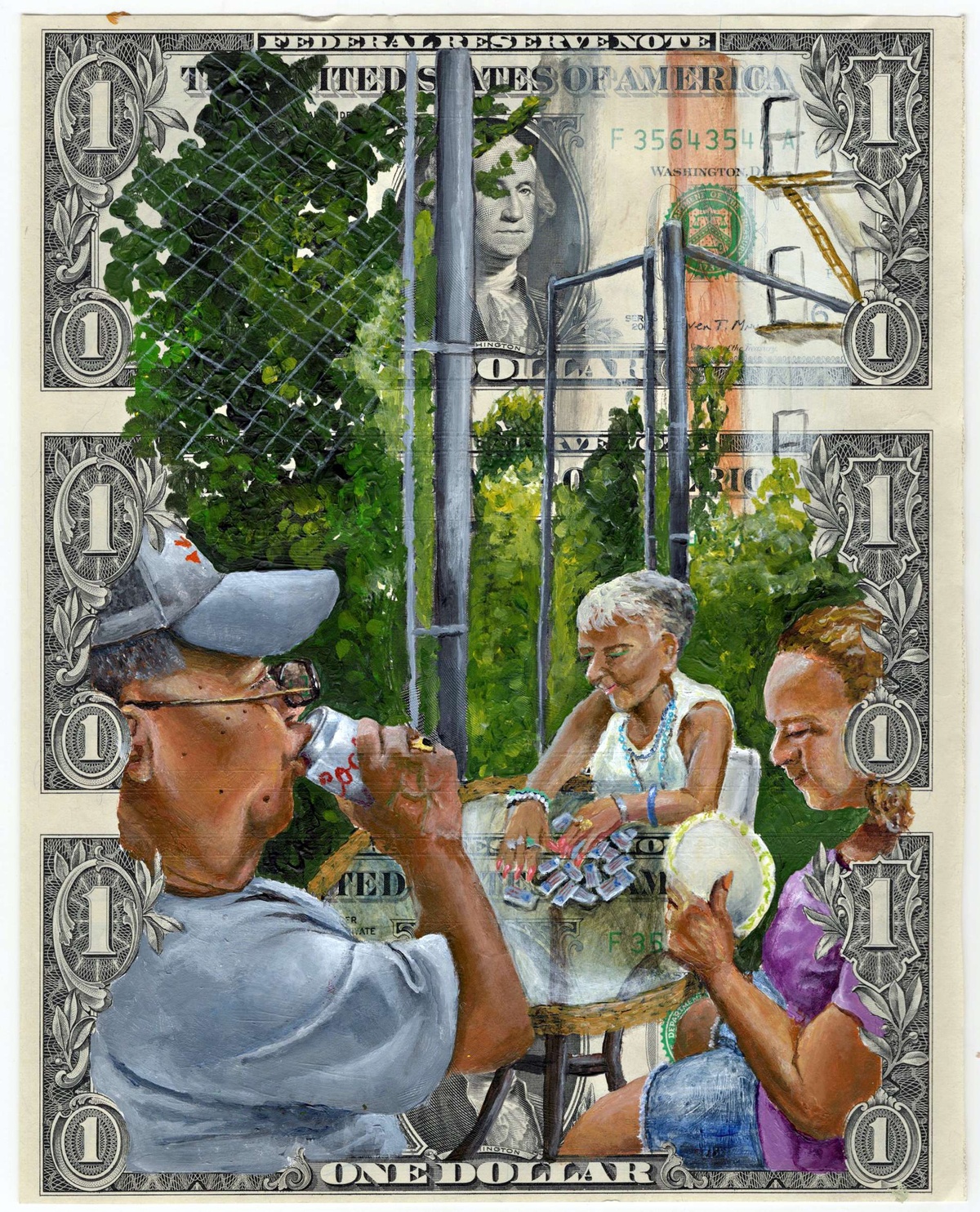

In Danielle De Jesus’s 7 stops to Manhattan from Jefferson Street (2022), a young girl looks apprehensively into a fenced community garden in Bushwick that has been adopted by, and marketed to, newcomers. The gate is open, but the girl, a Bushwick native, does not go in. The painting is one of a series of works De Jesus has made about the role of greenspaces—ranging from community gardens to her mother’s improvised garden on a fire escape—in Bushwick, where she grew up and from which her family was displaced by rising rents. The works are painted on stacked dollar bills, whose brick-like forms allude to the deep entanglements of finance and the built environment that contributed to the uprooting of her family. Another piece depicts a couple named Jose and Gina standing next to a casita and surrounded by Puerto Rican flags in La Finca community garden, which they steward. The garden abuts De Jesus’s childhood home, and she was moved to see it was still there on a recent visit back to the house. Snapshots of a neighborhood in flux, De Jesus’s works document how community gardens can be agents of both change and resilience.

This same tension pervades Matthew Schrader’s Ensemble (2018–22), a collection of photographs of Ailanthus Altissima trees he encountered on walks throughout New York City. The Ailanthus species (commonly known as “tree of heaven”) first came to the Americas in 1784, imported from China as sought-after decorative foliage for private gardens. Its reputation shifted over the ensuing centuries as the trees took root in new habitats, following the pathways of colonization and industrialization. Flourishing in disturbed and depleted soil—such as rubble-strewn lots and sidewalk cracks—able to clone themselves indefinitely, and almost impossible to kill, they are now regarded as weeds endemic to urban environments. Schrader’s images show the trees growing precariously, stubbornly, in the unlikeliest of places: amid piles of bricks, hugging chain link fences. They lend themselves to metaphor: artists such as David Hammons and musician Cecil Taylor have alluded to them in their works—a poetic history that Schrader builds on.

Schrader took a number of the images in Long Island City and along the Greenpoint waterfront, two of the most dramatically expanding and gentrifying neighborhoods in New York. The same shallow root structures that allow Ailanthus trees to thrive in neglected areas also make them well-suited to the active construction sites of those targeted by development. The trees, like many gardens, archive both disinvestment and areas of rapid expansion and gentrification—and the complex, interwoven nature of these economic and spatial forces. One of Schrader’s images, in fact, shows a tree sprouting from the foundation of PS1—a small reminder of the museum’s own scrappy past dating back to the days of the Brooklyn Bridge Event, as well as the impact it has had, as so many museums do, on the changing cityscape around it.

*

The varied artists and gardeners that have woven this history, a fraction of which is recounted here, are united by their interest in the overlooked spaces of the city, their subversion of conventional ideas of ownership, and their faith in the possibility of growth against the odds. Through approaches ranging from conceptual artworks to guerrilla gardening, they ask us to look more closely at the commonplace and neglected—the voids, the scraps, the weeds. The potential of a commons that community gardens offer, and the metaphor of freedom that they are burdened with, has become perhaps even more pressing as the climate crisis escalates, private interests infiltrate public space, and rents rise. As theorist Silvia Federici writes: “The very sense that we are living at the edge of a volcano makes it even more crucial to recognize that, in the midst of much destruction, another world is growing, like the grass in the cracks of urban pavement … affirming our interdependence and capacity for cooperation.” 66

Each of these practices is also fundamentally embodied: they emerge from walking, wandering, dancing, digging in the soil, lobbing seed bombs, exploring how life—human and nonhuman—can dwell in, thrive in, and transform the cityscape. Working with a cohort of girls from the Lower Eastside Girls Club, artist jackie sumell brings that embodiment to the courtyard of PS1 with a project called Growing Abolition. The multipart project, through which the girls explore connections between ecology and abolitionist thought, centers on a greenhouse scaled to the footprint of a solitary confinement cell in ADX Florence, a federal Supermax prison located in Colorado. The architectural plans for the greenhouse were informed by the lived experience of a man named Jessie, who is incarcerated at ADX and with whom sumell has been collaborating and growing with for seven years—planting gardens designed by Jessie from his space of confinement, out in the world. At PS1, the greenhouse becomes a space of hands-on transformation, where sumell and the girls grow seedlings and plants in collaboration with various gardens and organizations, including Green Guerillas, the North Bronx Collective, and Padre Plaza Success Garden. The project asks what plants can teach us about abolition, healing, and expanding our horizons of possibility— and considers how urban gardens can exist as expressions of love as much as resistance.

As I write this in May 2022, okra plants are growing in Long Island City. Lufa vines are starting to creep up the concrete walls of PS1. Pots of plantain—a common weed and powerful healing plant—remind us that the most overlooked life might be the most precious. More than anything, the project prompts recognition of what kinds of life are made invisible, and how to bring them to light. Atop a courtyard wall, not far from the greenhouse, sits a small sculpture by Puerto Rican duo Poncili Creación, best known for their raucous street performances and puppetry. 67 You might not notice the sculpture right away. It is a Dweller, one of a series of small sculptures inspired by garden gnomes that the artists have tucked in nooks and crannies throughout PS1 and beyond, in gardens and secret spots of New York. An homage to squatters past and present, these gnomes, as the artists state, “serve as decentralized shrines to honor human resilience against the pre- established norm.” 68 Taking up space can be a political act, as the many gardeners and activists that form this history teach us. The artists involved in these struggles suggest that so, too, is observing. Look closely at the cracks, the fissures, the gaps, and you might just find something growing there that, in its quietude, speaks volumes.

[1] As quoted in Vittoria Di Palma, Wasteland: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 13.

[2] For more on this history see Di Palma, Wasteland: A History. See also Silvia Federici, “Introduction to the New Enclosures,” Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (Oakland: PM Press, 2019), 26-34.

[3] “Digger Tracts,” www.diggers.org, accessed February 4, 2022, https:/www.diggers.org/digger_tracts.htm

[4] The term terrain vagues, coined in 1995 by architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales, refers to “seemingly abandoned or overgrown sites—where the landscape has gone to seed and been left to its own devices, is in suspended redevelopment, or is being furtively inhabited or otherwise used, under the radar of local authorities…” See Manuela Mariani and Patrick Barron, eds., Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale (New York: Routledge, 2014), 1.

[5] The exhibition shares its title with Jan Gehl’s Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space, first published in 1971, in which Gehl argues against the functionalism of city planning inspired by Le Corbusier in favor of a more organic perspective that takes into account “life between buildings as a dimension of architecture to be carefully treated.” See Jan Gehl, Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2011), 9.

[6] They even staged a “Death of Money Parade” in the streets of Haight Ashbury. “The Diggers,” www.diggers.org, accessed February 4, 2022, https:/www.diggers.org/overview.htm

[7] Their names were: Chino Garcia, Humberto Crespo, Angelo Gonzalez, Jr., Roy Battiste, Anthony Figueroa, and Sal Becker.

[8] For more on CHARAS, see R. Buckminster Fuller, Syeus Mottel, and Ben Estes, Charas. The Improbable Dome Builders (Brooklyn: Pioneer Works, 2018) and Nandini Bagchee, Counter Institution: Activist Estates of the Lower East Side (New York: Empire State Editions, An Imprint of Fordham University Press, 2018).

[9] As described by Chino Garcia during the talk “CHARAS: The Improbable Dome Builders, with Chino Garcia, Libertad O. Guerra, Matt Mottel, and Nandini Bagchee” (NY Artbook Fair 2018, September 2, 2018).

[10] Cara M. Jordan, “Directing Energy: Gordon Matta-Clark’s Pursuit of Social Sculpture,” in Gordon Matta-Clark et al., Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect (New Haven: The Bronx Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2017), 41.

[11] Matta-Clark would cite the interest neighborhood children had in this project in a letter addressed to NYC official Howard Stern, whom he was petitioning for permission to use city-owned buildings. See Gordon Matta-Clark, Gloria Moure, and Reina Sofía, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings (Barcelona: PolíIgrafa, 2006), 73. Matta-Clark’s short film Fire Child (1971) also documents his work beneath the bridge, focusing on the involvement and curiosity of local children.

[12]As Andrew Strombeck notes, such city-backed projects raised the city’s long-term debt by 48 percent between 1970–75. See Andrew Strombeck, DIY on the Lower East Side: Books, Buildings, and Art after the 1975 Fiscal Crisis (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2020), 31. For more on the fiscal crisis and the austerity measures put in place in its wake, see Kim Phillips-Fein, Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017).

[13] “Howard Cosell’s ‘the Bronx Is Burning’ Comments during 1977 World Series,” www.youtube.com, n.d., https:/www.youtube .com/watch?v=bnVH-BE9CUo.

[14] Francis X. Clines, “Blighted Areas’ Use Is Urged by Rohatyn,” The New York Times, March 16, 1976, sec. Archives, https:/www.nytimes.com/1976/03/16/archives/blighted-areas-use-is-urged-by-rohatyn.html.

[15] Bagchee, Counter Institution, 200.

[16] Laura J. Lawson, City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 2.

[17] Lawson, City Bountiful, 38.

[18] Artist Fritz Haeg has recently taken up this history in his artwork Edible Estates (2004–2014).

[19] Lawson, City Bountiful, 21.

[20] This photograph is featured in Aki Onda’s project Silence Prevails: Lower East Side Community Gardens During the Pandemic, 2020/2022.

[21] For more on how these metaphors were used in efforts toward redevelopment and gentrification, see Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London; New York: Routledge, 1996) and Christopher Mele, Selling the Lower East Side: Culture, Real Estate, and Resistance in New York City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000).

[22] Eds., “Hattie Carthan: Roots Grow in Brooklyn,” Heresies 13: Feminism & Ecology, January 1, 1981: 32.

[23] Miranda J. Martinez, Power at the Roots: Gentrification, Community Gardens, and the Puerto Ricans of the Lower East Side (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2010), 46.

[24] Martinez, Power at the Roots, 42.

[25] Incorporated into a non-profit in 1976, Green Guerillas continues to play an active role in supporting community gardeners throughout the five boroughs. The organization is featured in Growing Abolition by jackie sumell & The Lower Eastside Girls Club in the PS1 courtyard.

[26] “Our History,” Green Guerillas, n.d., https:/www.greenguerillas.org/history.

[27] Though it was among the first, this designation likely has come about because it was the most legible to city officials and press. Christy engaged municipal organizations and it was in part due to her efforts that the city began recognizing community gardens, starting GreenThumb in 1978.

[28] Bleecker Times, Vol. 1, No. 1, December 1973.

[29] For a longer discussion of conflicts between Puerto Ricans in the Lower East Side and groups who had more recently moved into the area, including artists, see Martinez, Power at the Roots.

[30] The full extent of the kinds of making and presenting of art that has occurred in community gardens is outside the scope of this exhibition and essay, and merits further scholarship.

[31] Trees were a central theme in Matta-Clark’s work. “People live in rearranged trees,” he once stated, an unraveling of standard understandings of the built landscape typical of his practice. See Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings, 345.

[32] A New York Times article from 1973 includes interviews with purchasers of lots at one such city auction, including Matta-Clark. See Dan Carlinsky, “‘Sliver’ Buyers Have a Field Day at City Sales,” The New York Times, October 14, 1973, sec. Archives, https:/www.nytimes.com/1973/10/14/archives/sliver-buyers-have-a-field-day-at-city-sales-sliver-buyers-have.html.

[33] Jeffrey A. Kroessler, “Gordon Matta-Clark’s Moment,” in Gordon Matta-Clark et al., Odd Lots: Revisiting Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Fake Estates” (New York: Cabinet Books, in conjuction with The Queens Museum of Art and White Columns, 2005), 36.

[34] Quoted in Gordon Matta-Clark et al., Odd Lots: Revisiting Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Fake Estates”, 65.

[35] Matta-Clark has been criticized, at times rightfully so, for failing to take into account the actual needs of the people living in neighborhoods where his projects were located, but his works in the mid-1970s demonstrate an increasing social and political consciousness.

[36] Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings, 69

[37] Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings, 69. In 1977, Matta-Clark received the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship for the Resource Center and Environmental Youth Program for Loisaida.

[38] This information was confirmed by various sources. Jane Crawford (widow of Gordon Matta-Clark and Co-Director of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark), in conversation with the author, April 2022. Carolyn Ratcliffe (former President of La Plaza Cultural), in conversation with the author, February 2, 2022. G.H. Hovagimyan (former assistant to Gordon Matta-Clark), in conversation with the author, April 18, 2022.

[39] Cecilia Vicuña, interview with Jody Graf, “Cecilia Vicuña on her Sidewalk Forests,” November 23, 2021, www.momaps1.org/post/52-cecilia-vicuna-on-sidewalk-forests

[40] Architects including Lebbeus Woods, Neil Denari, Shin Takamatsu, Diller+Scofidio, Imre Makovicz, Dan Coma, and BA BA ARC submitted proposals to a 1984 exhibition at the Storefront for Art and Architecture titled Adam’s House in Paradise that presented alternatives to the city’s plans.

[41] The tree became an artwork subsequently presented in the exhibition Webutuck Vuitton at The Re Institute, 2017.

[42] Whitney Kimball, “The ABC No Rio Interviews: Peter Cramer and Jack Waters,” Art F City, August 1, 2012, http:/artfcity.com/2012/08/01/the-abc-no-rio-interviews-peter-cramer-and-jack-waters/.

[43] The event was held as part of Creative Time’s Art on the Beach programming.

[44] For more on the interaction of the AIDS crisis and gentrification in the 1980s, including an in-depth discussion of Peter Cramer and Jack Waters, see Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination (Berkeley, Calif.: California University Press, 2013).

[45] Manuel Castells and John Mollenkopf, “Conclusion: Is New York a Dual City?”, in John H Mollenkopf and Manuel Castells, eds., Dual City: Restructuring New York (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1991), 400.

[46] Bagchee, Counter Institution, 143.

[47] Lawson, City Bountiful, 237.

[48] The renovation of the park is seen by some as a direct response to a 1988 riot—one of many in the park’s history—to try to prevent further uprisings. For more on the Tompkins Square Park riots, see Paper Tiger TV, “Tompkins Square Park: Operation Class War on the Lower East Side,” 1992, https:/vimeo.com/165919731?embedded=true&source=vimeo_logo&owner=4326850.

[49] Diana Balmori and Margaret Morton, “Preface,” Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives (Yale University Press, 1995).

[50] Diana Balmori and Margaret Morton, Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives, 29.

[51] Chin worked with feng shui practitioner Thay Boi Trung and writer Sarah Rossbach.

[52] For more on the community that lived at The Hill, see Balmori and Morton, Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives, and Gabriele Schafer, The Hill (Brooklyn, New York: Autonomedia, 2021).

[53] Tom Burr et al., Tom Burr: Extrospective: Works, 1994-2006 (Lausanne: Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts De Lausanne, 2006), 12.

[54] Burr was influenced in his thinking by Robert Smithson’s writings on Central Park. See Robert Smithson, “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical. Landscape,” Artforum Vol. 11, No. 6 (February 1973): 62.

[55] For more on the ways in which preservation has been marshalled towards development in New York City, see Rosalyn Deutsche, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Chicago, Ill.: Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in The Fine Arts; Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002).

[56] See Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (New York: New York University Press, 2001).

[57] Michael Grunwald, “Mayor Giuliani Holds a Garden Sale,” Washington Post, A1, May 12, 1999.

[58] Giuliani ended up making a deal with Trust for Public Land and New York Restoration Project, founded by Bette Midler, who bought the land under a number of the threatened gardens for 4.2 million dollars.

[59] “History of the Community Garden Movement: NYC Parks,” www.nycgovparks.org, accessed February 11, 2022, https:/www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/community-gardens/movement. This is the official count. It is likely that there are many more unaccounted for.

[60] For example, The North Bronx Collective started a community garden at Tibbett’s Tail in the Bronx, which they were locked out of by the city in 2021. Hakim Bishara, “Bronx Artists Collaborated to Refurbish Community Park until the City Locked Them Out,” Hyperallergic, April 6, 2021, https:/hyperallergic.com/632855/north-bronx-collective-refurbish-tibbetts-tail-nyc-parks-locked -out/.

[61] The average rent for a one-bedroom in the Lower East Side, for example, is currently $3,269. The poverty line threshold in New York City is $36,262 in annual income for a household of four. In 2019, 17.9 percent of New Yorkers lived below the poverty line. Another 40.8 percent lived near poverty. See “New York City Government Poverty Measure 2019: An Annual Report from the Office of the Mayor,” 2019, https:/www1.nyc.gov/site/opportunity/poverty-in-nyc/poverty-measure.page.

[62] In 2014, a two-square foot property on West 116th Street was valued by the city at $19,000. Gary Buiso, “Inside the City’s Tiniest Properties,” New York Post, August 24, 2014, https:/nypost.com/2014/08/24/inside-the-citys-tiniest-properties/.

[63] In 1996, Mayor Giuliani switched from standard foreclosure to a tax lien process: if you fail to pay property taxes, an individual investor purchases the right to the property and the taxes owed, inviting private speculation on debt and removing the possibility that the city would end up with a surplus of empty lots and buildings—the very condition that made so many community gardens possible in the first place.

[64] See, for example, the struggle around the preservation of Children’s Magical Garden in the Lower East side. Ed Litvak, “Children’s Magical Garden Wins a Court Battle against Developers | the Lo-down : News from the Lower East Side,” Thelodownny.com, July 16, 2018, https:/www.thelodownny.com/leslog/2018/07/childrens-magical-garden-wins-a-court -battle-against-developers.html.

[65] Another tactic used to prevent claims of adverse possession is to close “public” spaces for one day a year, as Columbia University does, guaranteeing that no one could have continuously occupied the space. David W. Dunlap, “Closing for a Spell, Just to Prove It’s Ours,” The New York Times, October 29, 2011, sec. New York, https:/www.nytimes.com/2011/10/30/nyregion/lever-house -closes-once-a-year-to-maintain-its-ownership-rights.html.

[66] Silvia Federici, “Introduction,” Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (Oakland: PM Press, 2019), 1. Federici has noted that community gardens are crucial to the idea of a new commons: “Most important has been the creation of urban gardens, which spread across the country in the 1980s and 1990s, thanks mostly to the initiates of immigrant communities from Africa, the Caribbean, or the South of the United States. Their significance cannot be overestimated.” See Federici, Re-Enchanting the World, 105.

[67] Poncili Creación will perform No gods only flowers at MoMA PS1 on July 29 and 30, 2022. The performance is a visual poem enacted by larger-than-life puppets suspended from construction cranes above PS1’s Courtyard, with live musical accompaniment.

[68] Poncili Creación, email to the author, May 22, 2022.