On Bungkalan and Butterflies

- Interview

For over a decade, artists Enzo Camacho (Filipino, b. 1985) and Ami Lien (American, b. 1987) have amplified local forms of survival and resistance, with particular attention to the Philippines. On the occasion of their first major US museum exhibition Offerings for Escalante, on view at MoMA PS1 through February 17, the duo discuss their historical and material research on the island of Negros, with both documentary and indexical approaches to embodying the land. Camacho and Lien’s interests materialize in two of their recent works on view in the exhibition, Langit Lupa (2023) and Decomposition Animation (2023), which recently entered the collection of The Museum of Modern Art. The conversation with Chief Curator Ruba Katrib triangulates the social and environmental concerns of artists and activists across The Philippines, its diaspora, and New York.

Ruba Katrib: Let’s talk about the film Langit Lupa, which is a new commission between MoMA PS1, Para Site, CCA Berlin, and the Glasgow International. How did you embark on this piece, and when did it start coalescing for you?

Enzo Camacho: The film comes out of work we have been doing on the Philippine island Negros, since around 2017. Negros is known as the primary sugar-producing region of the country, and we have been trying to understand the local plantation economy, the political issues surrounding it, and the forms of people’s resistance that have been challenging that system. A turning point for us occurred on October 20, 2018. On this day, a massacre of protesting farm workers took place in Sagay, a city we had previously visited during our first research trip together. The 2018 Sagay Massacre clarified the reality of the situation. From that moment, the research began to encompass the forms of repressive violence that really constitute the basis of the plantation economy.

Ami Lien: The bungkalan movement came into focus in our research. Bungkalan means “to till” or “to cultivate” in Filipino. Within this movement, plantation worker families—who have usually been waiting for decades for their land to be redistributed to them legally—have self-initiated their claim to unused plantation property and started to farm it themselves, using indigenous and agro-ecological methods, in order to grow food crops such as rice and vegetables to feed their families and communities. In the case of the Sagay Massacre, a group of organized farmer families were in the process of setting up a bungkalan when masked gunmen showed up and fired at their tent. Nine people were killed.

Enzo Camacho: Our film Langit Lupa focuses on a more historical incident, the 1985 Escalante Massacre, but really as a way to talk about the current situation.

Ruba Katrib: These recent events sound so much like the massacres of land defenders around the world, drawing attention to just how far-reaching this quiet war against environmental activists has become. In the paper works in Offerings for Escalante, there is a kind of re-pollination that reintroduces the diversity inherent to the land itself. Can you speak more to the process of creating these artworks?

Ami Lien: Bungkalan as a social movement really became an inspirational logic for our art practice. A few months after the Sagay Massacre occurred, we visited a community cultural center in a coastal neighborhood in Sagay, where a local activist had organized a paper-making workshop for the women in this community, who were mostly the wives of fishermen. This workshop was very formative for us, because we learned that you could make paper using almost any kind of fibrous plant material, using very simple tools. We started incorporating paper making into our artistic practice on the island, using sugarcane fibers and the waste materials from other local plants. The process felt analogous to composting, which is also utilized in the organic farming methods of the bungkalan movement.

Ruba Katrib: The cycles of life and death also recur in the way images transfer from one into the other in the film Decomposition Animation. How are you using symbolism to invoke these natural rhythms?

Ami Lien: The butterfly really emerged as an interesting symbol of change. My cultural background is Taiwanese-Chinese, and what we share with Filipino culture is a belief in the butterfly as this creature that exists at the interstices of the living and the dead worlds. When you see a butterfly in your house it means that a deceased friend is visiting you. We started amassing butterflies in our work so that they begin to draw this collective force, almost like a queer communist army for an imagined future.

Enzo Camacho: In our recent work, we have been thinking a lot about images that have a simplicity to them as symbols. I think anyone who walks in and sees a skull, or a butterfly, or a flame, or a heart will have some association with it. They’re nice entry points because they’re so open—in the animation, for example, the heart is rendered in three different ways: a sacred heart, an anatomical heart, and a simple child’s drawing of a heart. These seemingly elementary images can open up so many spaces.

Ruba Katrib: The complexity of trying to achieve simplicity really comes through in Langit Lupa. 16mm phytograms appear while you’re hearing someone tell their story, instead of seeing a talking head. This strategy reinforces that these stories are carried by dirt, animals, and people, and thus embedded within the land.

Ami Lien: I feel like plants and people are allied in resisting the plantation system. The phytogram technique creates these spectral, sensual flickering sequences, and we wanted to experiment with how this kind of imagery can prepare a body to listen to something that is quite difficult. While we’ve been very influenced by experimental and structural film, and the role abstraction plays within them, we also wanted to push the medium forward in terms of how it can agitate and mobilize its audience politically.

Enzo Camacho: When we filmed the interviews, a couple of people said they preferred not to be visible in the film, so we decided to make that a blanket logic. The phytogram imagery became a stand-in for our interview subjects, while also highlighting how this specific historical event, the Escalante Massacre, is embedded in a much longer history of the land. It’s also why we started the film with a narrative of the deforestation that paved the way for the plantation economy.

Ruba Katrib: In lieu of an origin point, it is important to look back at the 1985 Escalante Massacre as a recent historic period in which issues of resource extraction were front and center, issues that are still ongoing and even accelerating.

Enzo Camacho: This is a story about a massacre, but it’s also a story of an incredible mass protest, an incredible feat of organizing and mobilizing thousands of people on this island to resist their conditions. We should never lose sight of this…

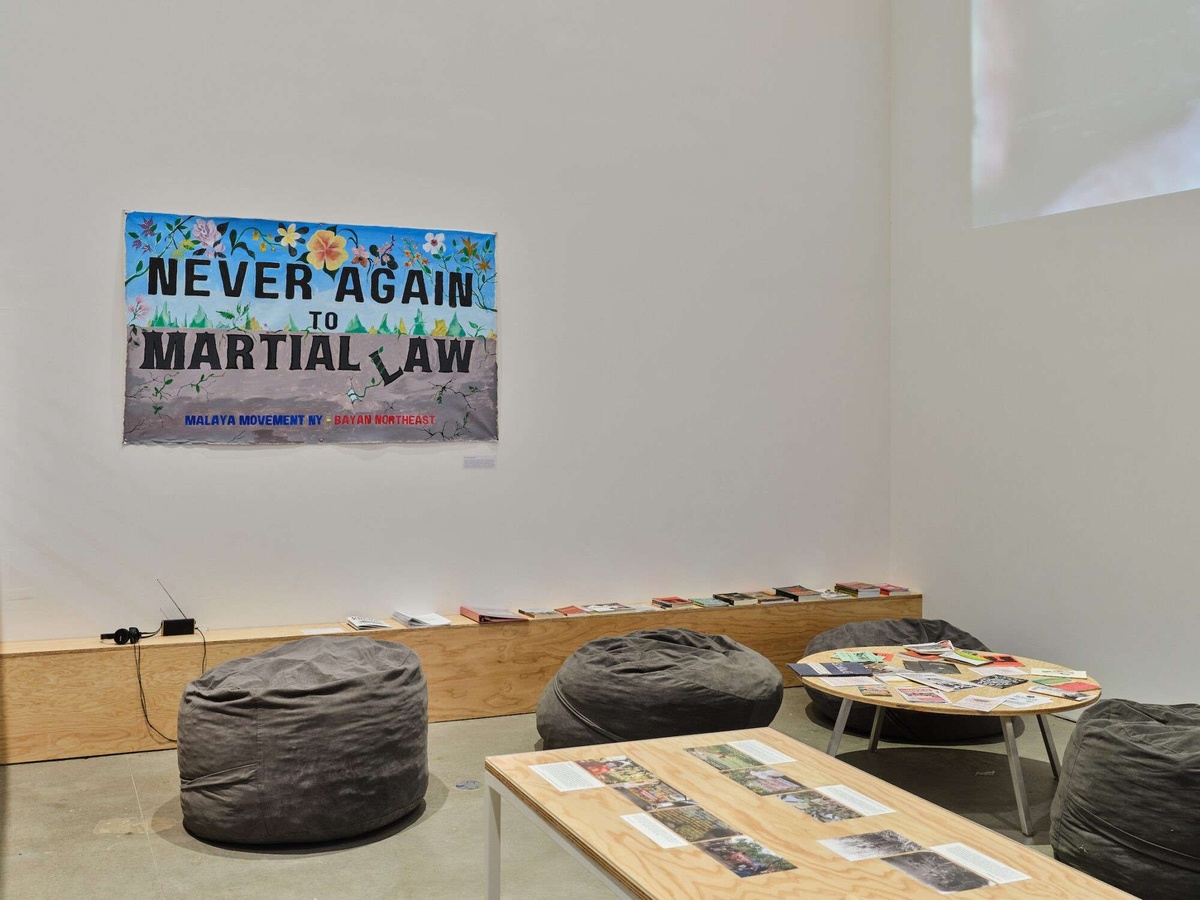

Ruba Katrib: There is both historical resistance and continued resistance. In this exhibition, it’s notable that you’re documenting the histories and making visible their present-day ramifications. In the double height gallery, you’ve invited groups such as BAYAN USA Northeast, Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP), Dang A Dang Radio, Malaya Movement New York, Sama-samang Artista Para sa Kilusang Agraryo (SAKA), and Unyon ng Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (UMA) to participate in a cross-cultural dialogue. In this installation, Our Creativity Belongs to the Masses (2024), you’ve highlighted what’s happening between the local, the diaspora, Queens, New York, and the Philippines.

Enzo Camacho: In a way, the diaspora is also a result of the colonial plantation system. The mass outbound labor migration from the Philippines is because of chronic poverty, persistent underdevelopment, political persecution that are all direct products of land monopoly in general.

Ami Lien: A lot of the problems we’ve been witnessing firsthand in Negros can be traced directly back to United State’s period of colonial rule and ongoing imperial intervention. Our Creativity Belongs to the Masses was an opportunity to surface these connections for a US-based audience.

Enzo Camacho: Yeah, the lines are so direct. The US is still the number one imperialist power controlling lives in the Philippines. The exhibition is a great platform to highlight the work of US-based organizations like BAYAN USA and Malaya Movement, who are carrying out important campaigns that would directly help the situation in Negros, such as the Philippine Human Rights Act.